Espoo Museum of Modern Art

Mobile Guide to the Exhibition Arte Povera – A New Chapter

In this mobile guide, you will find texts about each of the 21 artists in the exhibition, as well as images of selected works. In addition, at the bottom of the page, there is a list of contributors and acknowledgments.

The term Arte Povera, literally meaning “poor art”, refers to a movement that emerged in Italy in the late 1960s, when artists began creating works from discarded and modest everyday materials. Their aim was to challenge the art market of the time and bring artistic practice closer to daily life.

Although Arte Povera is traditionally regarded as a male-dominated movement, this exhibition focuses on the transgenerational role of women in shaping and establishing it as part of international contemporary art. The exhibition features both the original members of the movement and contemporary artists.

Featured artists

Beckmann, Liisi

Liisi Beckmann (1924–2004) was a Finnish designer and artist best known for the Karelia chair she designed for the Italian brand Zanotta in 1966. Beckmann lived and worked in Italy from 1957 to 2003, and from the 1970s onwards she focused primarily on visual art. The influence of Arte Povera, particularly its emphasis on recycled materials, is evident in many of her works, which incorporate yarn, fabric and paper. Her compositions often explore themes related to gender and the body. The textual quotations in the works can be interpreted as the artist’s reflections on her own identity.

Bourgeois, Louise

Born in France, Louise Bourgeois (1911–2010) moved to the United States in her late twenties. She turned to art as a way to process traumatic experiences and to examine the fundamental aspects of life: love, hate, birth, death and sexuality. Cell XIX (2000) is part of a larger series based on the contents of her own wardrobe. According to Bourgeois, clothes represent a merging of cultural conventions, personal experiences and memories. For Bourgeois, her sculptures were equivalent to her own body and the emotions experienced through her creative process. The form of Cell XIX can be read as both a prison and a safe haven, preserving the lived emotions.

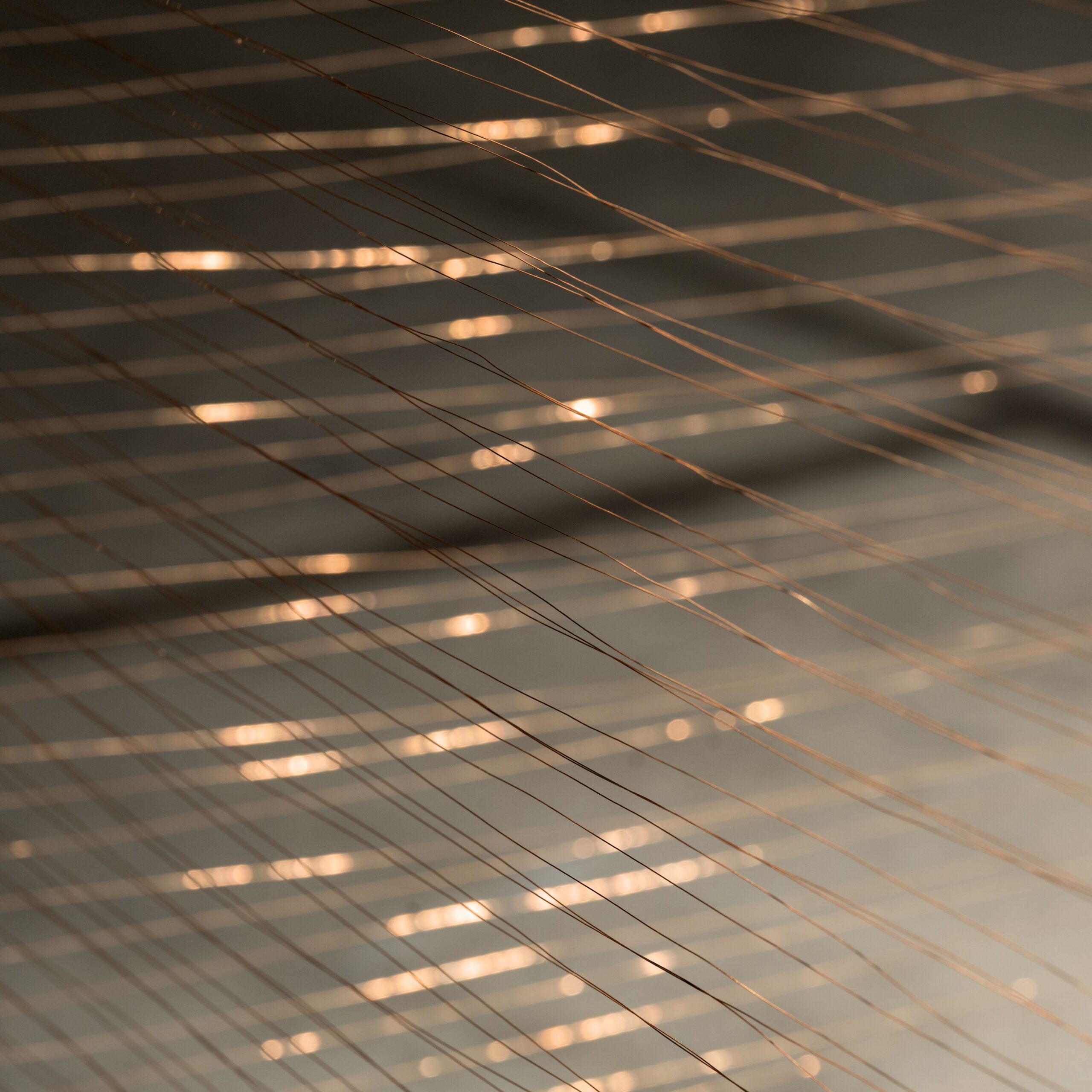

Ducrot, Isabella

Italian artist Isabella Ducrot (b. 1931) creates painted collages using antique fabrics and Japanese paper sourced from across Asia. Balancing between figurative and abstract forms, her works depict women’s clothing and everyday textiles. Ducrot is particularly drawn to ordinary printed fabrics and their basic structure, the lattice of warp and weft. She believes that checkered cloth in particular is historically associated with women’s care work, the poor and the marginalised. To her, however, the most unassuming fabrics have a familiarity that makes them almost like our second skin, giving these universally shared materials an undeniable intrinsic value.

Grisi, Laura

Born in Rhodes, Greece, Laura Grisi (1939–2017 worked between Rome and New York. Influenced by kinetic and op art, she initially explored movement and visual illusions but shifted towards a more immaterial approach in the late 1960s. During her travels in Africa, Asia, North America and Oceania, she began studying natural phenomena such as wind, light, fog and water. Employing a range of techniques, Grisi sought to represent these phenomena and reconstruct sensory experiences of them without reducing them to mere objects. The work Vento di Sud-Est (Wind Speed 40 Knots) on display focuses on wind. It was first shown at La Tartaruga gallery in Rome in 1968.

*At EMMA, the technical and spatial reconstruction of the original installation is realised according to instructions from Haus der Kunst, following their art historical research on the work.

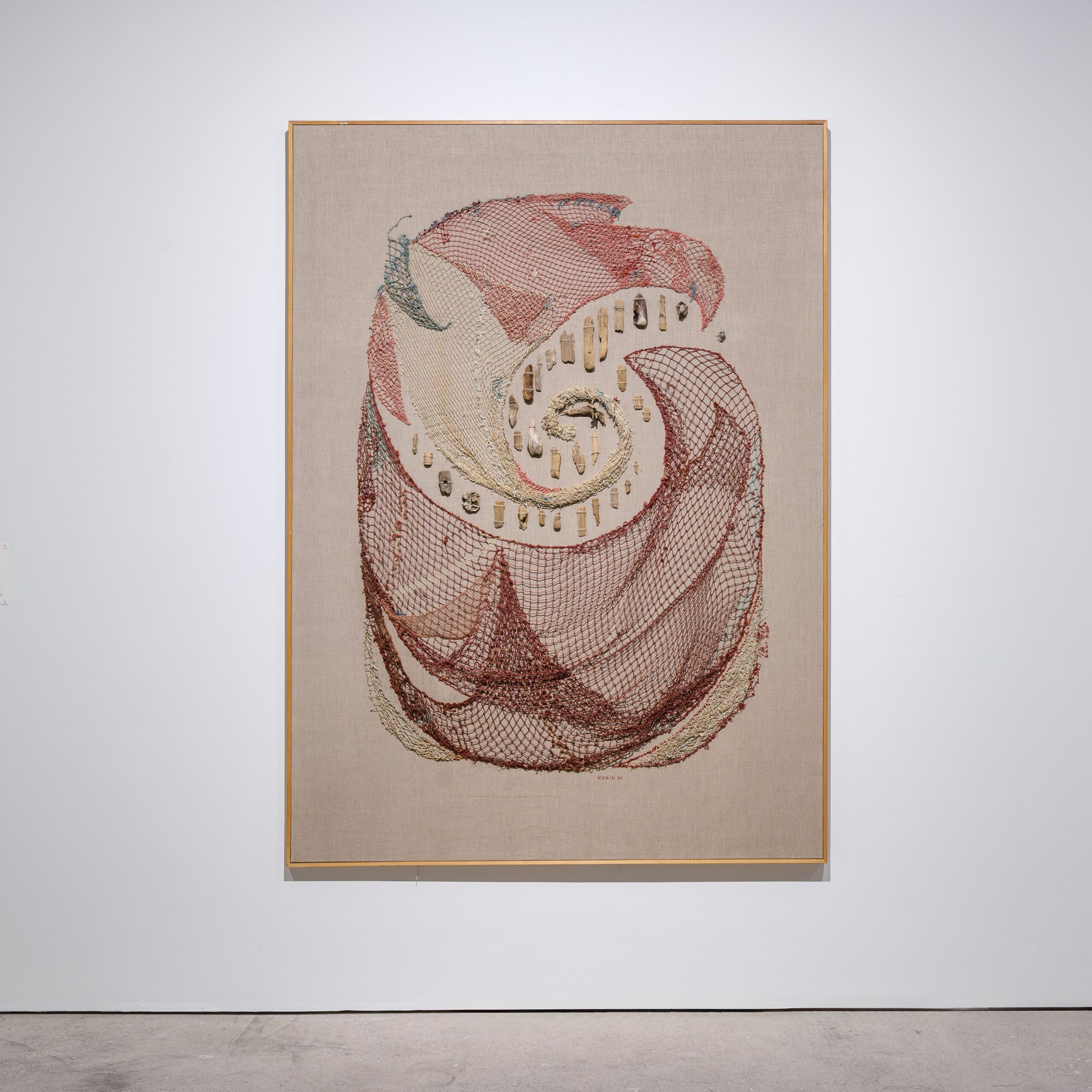

Hellman, Karin

Finnish artist Karin Hellman’s (1915–2004) collages draw inspiration from the modest and ecological elements of Arte Povera. Her collages were exhibited in France as early as the 1960s. During her travels in France and elsewhere in Europe, Hellman came into direct contact with the European art scene. Nixie’s Waltz (1988) features the spiral motif frequently found in her works. While playing with materials and forms, Hellman often embeds an everyday or mythical narrative in her works. In this work, Nixie, the water spirit in Scandinavian folklore, is crafted from cotton netting and seashells.

Hesse, Eva

Eva Hesse (1936–1970) was a German-born American artist who pushed the limits of sculpture. She became known for her experimental use of unconventional materials such as latex, fibreglass, wax and papier-mâché. The fragile materials and irregular shapes in her works evoke decaying, organic matter. These sculptures, referred to collectively as studioworks, call to question the distinction between finished artwork and technical exploration. The series demonstrates Hesse’s spontaneous and unconventional approach, and her desire to capture the very essence of the materials that she explored.

Kaikkonen, Kaarina

Kaarina Kaikkonen (s.1952) is a Finnish sculptor known for her large installations and textile works. Her most frequently used materials are men’s shirts, suit jackets and ties. For Kaikkonen, the suit jacket initially symbolised her father but has since come to signify humanity more generally in her work. The use of countless recycled clothes can be seen to reflect the anonymity of crowds but also the individuality of each of the clothes’ former owners.

Kalsmose, Mille

In her work Conscious Matter (2018), Danish artist Mille Kalsmose (b. 1972) examines human life as part of the cosmos through the chemical element of iron. Iron appears in the work in various forms as powder, iron ore and blood, highlighting its presence in the human body and the universe. The work presents iron as an element that enables life while also constraining its conditions like a cell-like structure.

Katz, Bronwyn

The backdrop of Bronwyn Katz’s (b. 1993) work is the political context of South Africa, where indigenous languages, cultures and environments have been devastated by European colonialism. For Katz, the bed serves as a symbol through which they explore the themes of homelessness, belonging and the concept of land. The pot scourers covering the bedsprings refer to the notion of a labouring Black body, as perpetuated by white colonial narratives. The title of the work – |ui !nans (one hailstone) – comes from the endangered !Ora language and carries two meanings: last-born and hailstone. It refers to a text by language activist Andries Bitterbos, Rain and Drought (1936), which describes the ritual of placing a single hailstone under the tongue of a family’s last-born child to end a hailstorm.

La Rocca, Ketty

Ketty La Rocca (1938–1976) is recognised as one of the foremost pioneers of body art and visual poetry. She explored language, gestures and the visual representation of women in 1960s and 1970s Italy. La Rocca’s Craniology series (1974) is based on X-rays of her skull taken during the ten years of her battling cancer. The series is an exploration of La Rocca’s own mortality conveyed through complex, dramatic self-portraits. The works add new layers of meaning to the original function of the X-rays while also preserving the recognisable intimacy of the images.

Lai, Maria

Sardinian artist Maria Lai (1919–2013) drew inspiration from the multimaterial expression of Arte Povera in her explorations of local identity, myth and folklore from the late 1960s onwards. Thread, stitching and interactivity became the key elements of her art. Her works such as interlocked canvases and looms, stitched books and embroidered, fictional maps evoke ideas of locality in relation to the vastness of the surrounding world. The social and educational role of art was expressed in many of the public artworks that Lai created with the local community in Sardinia.

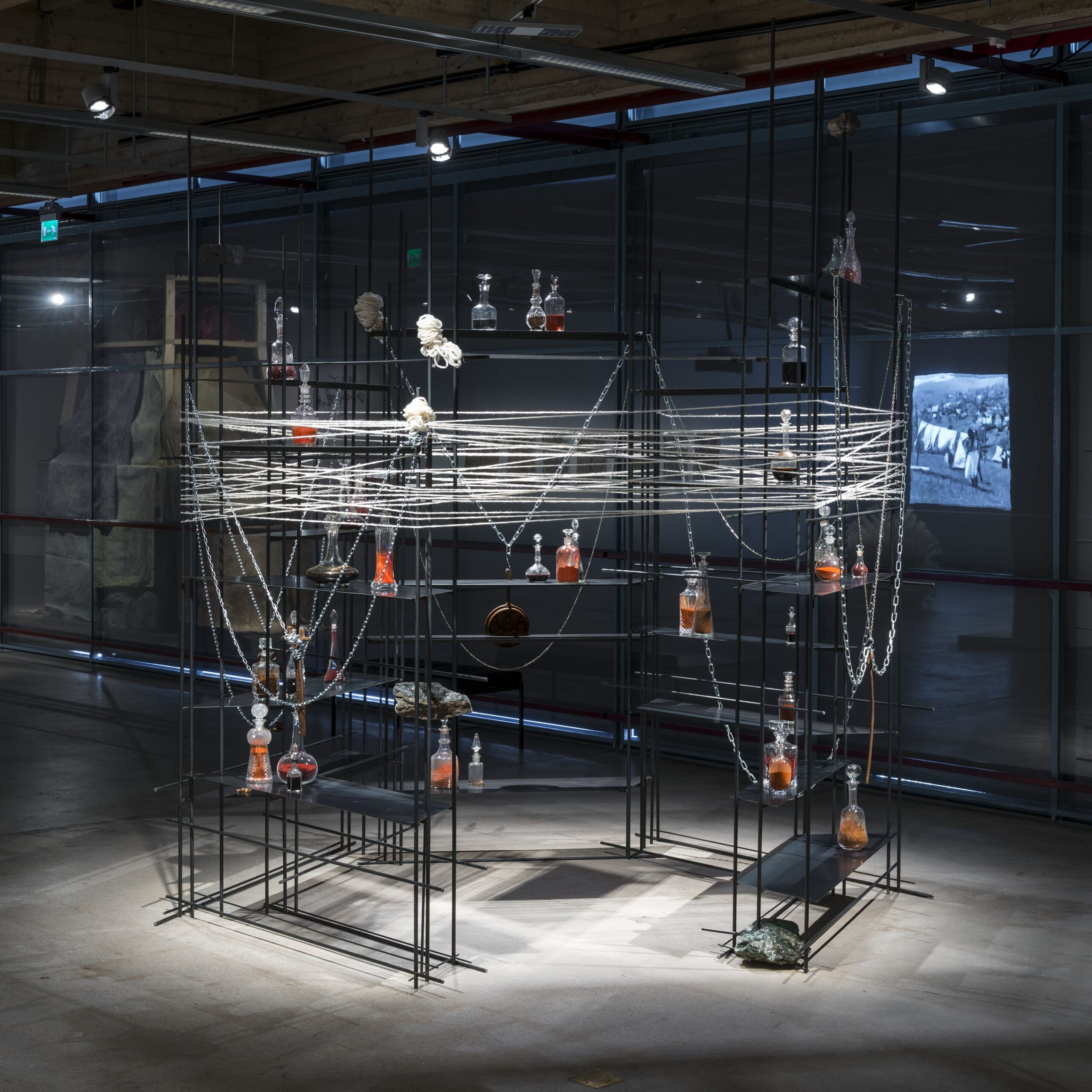

Lupaș, Ana

Ana Lupaș (b. 1940) is a Romanian artist renowned for her use of everyday materials such as wool, cotton and hemp. Through her chosen materials, she reflects the harsh realities of life under the communist regime of Nicolae Ceaușescu*. In defiance of the artistic norms imposed by the state, Lupas organised a clandestine artistic community that challenged the government’s ideological restrictions. Her series Identity Shirts (1969) consists of second-hand shirts marked by signs of time and wear. Also on display are photographs of Humid Installation (1970/2024), a collective performance in which wet linens were hung to dry in the Romanian countryside. Rather than a permanent monument, this work was an ephemeral installation created in collaboration with local farmers. It addressed the interplay between history, community and local custom, while calling attention to fading rural traditions and the significance of daily manual labour.

*Nicolae Ceaușescu (1918–1989) was the communist dictator of Romania from 1965 until his execution during the Romanian revolution.

Merz, Marisa

Works by italian artist Marisa Merz (1925–2019) were included in the first Arte Povera exhibitions in Italy in the late 1960s. The interplay between her roles as an artist, wife and mother were reflected in her creative process. Merz favoured materials that could be easily worked with at home, such as aluminium and copper wire. She often left her works untitled and undated, and reworked them to create varying improvised compositions. Merz’s oeuvre does not form a linear sequence of independent works; instead, each piece is reimagined within the context of the space in which it is displayed.

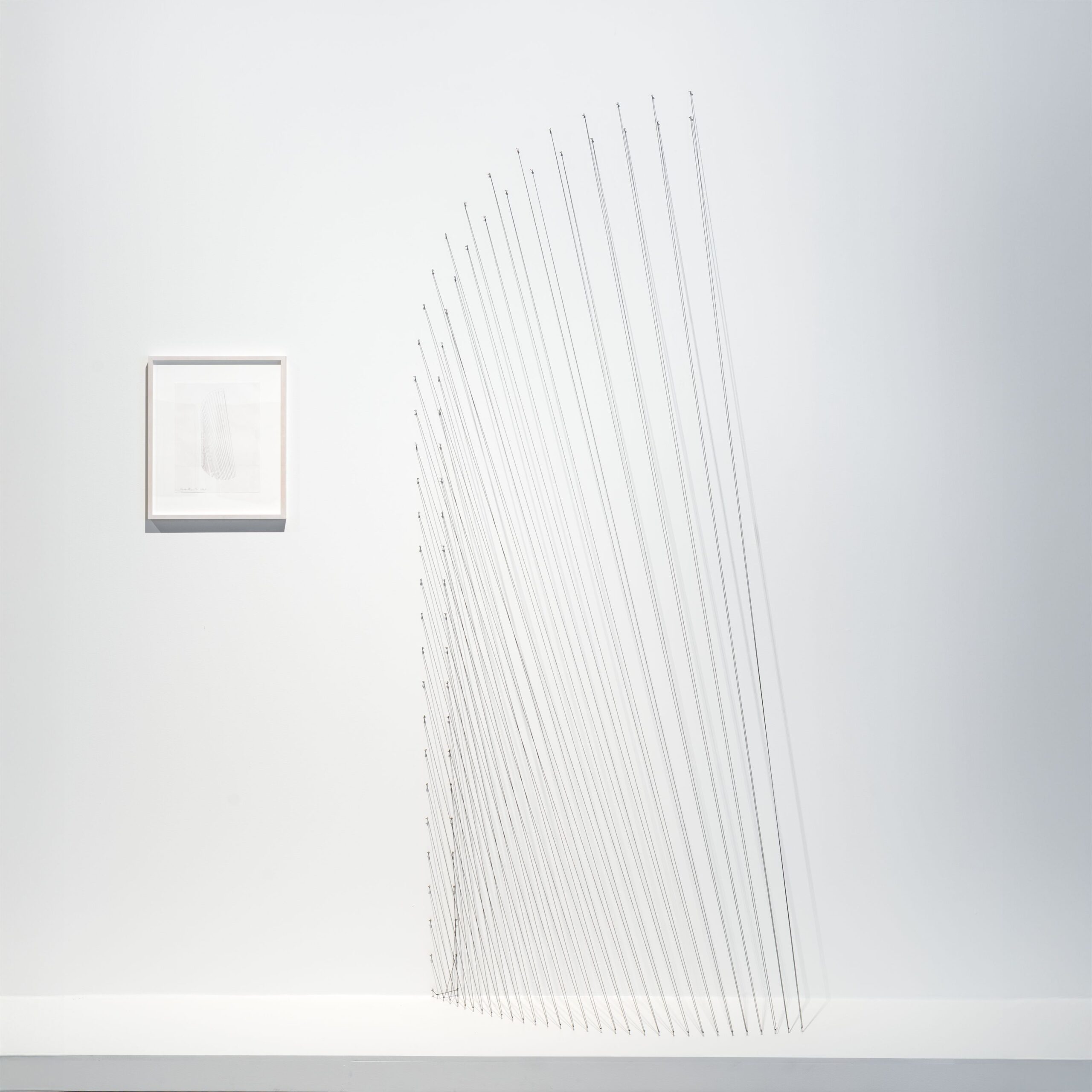

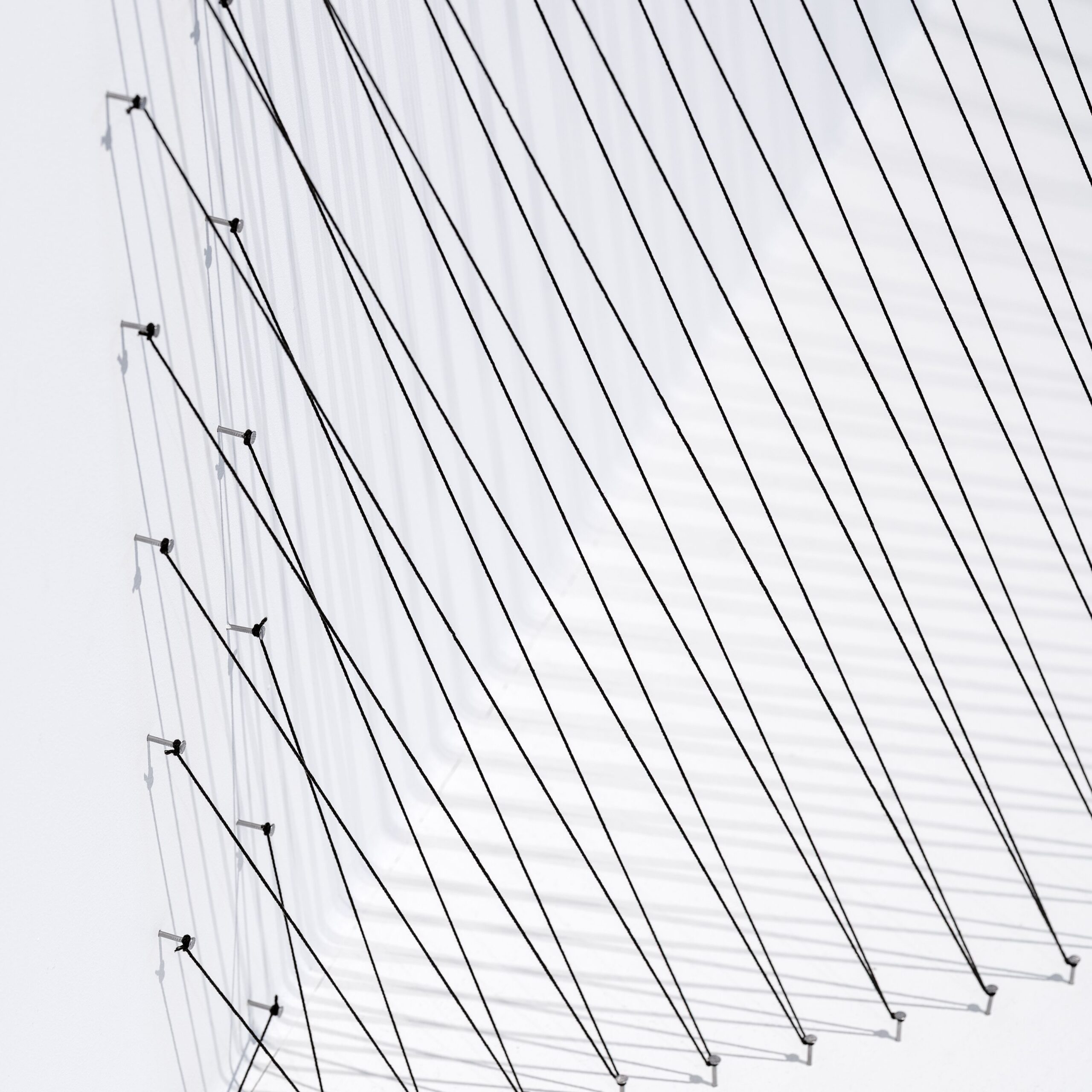

Miyamoto, Kazuko

Kazuko Miyamoto (b. 1942) is known for her compositions of thread and nails, transforming drawn lines into three-dimensional forms. Born in Tokyo, Miyamoto has worked in New York since the 1960s as part of the local feminist artist community. While her work is influenced by mathematically oriented minimalism and its emphasis on repetition, Miyamoto has also challenged its mechanical nature by incorporating in her works subtle irregularities and visible human touch. Her works highlight the creative process and the unique qualities of each found material that she employs.

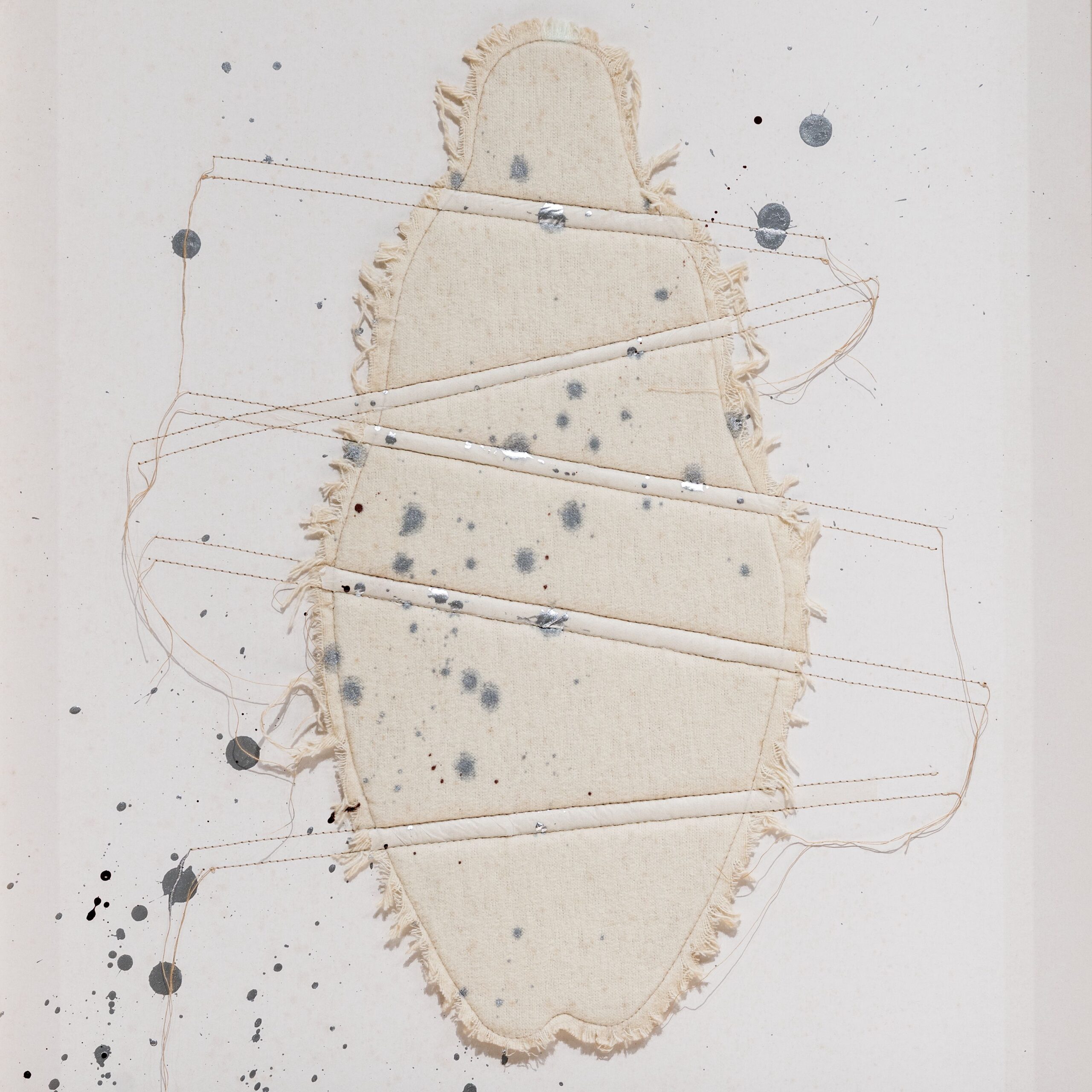

Nasser, Dala

Lebanese artist Dala Nasser (b. 1990) challenges the traditions of landscape painting while exploring sites where ancient history, geopolitics and everyday life intersect. This work echoes the shape of Hiram I’s tomb in Southern Lebanon. The painted fabrics bear impressions of the tomb’s facade and are steeped in pigments from plants found growing around the tomb. Hiram I, the king of the Phoenician city of Tyre, ruled from 980–947 BCE in the area of present-day Lebanon and was a key ally to the kings of Israel. Today, his tomb sits by a highway near the village of Qana, a place associated with Jesus’s first miracle and civilian massacres brought on by Israeli military invasions in 1996 and 2006. For Nasser, the tomb encapsulates how every event is inevitably entangled in a complex web of history.

Nengudi, Senga

The practice of American artist Senga Nengudi (b. 1943) merges experimental sculpture with object-related performance, attaching new meanings to everyday materials. One of her best-known projects is the ongoing R.S.V.P. series, which she began in the 1970s. It encompasses dozens of installations fashioned from nylon stockings, sand and metal objects. Some of these works are activated with live performances, in which the elastic nylon bends and stretches in response to a dancer’s movements. Initially conceived as an exploration of the body’s capacity for change during pregnancy, the series has also come to symbolise political resilience and perseverance. Throughout her career, Nengudi has focused on examining the struggles of Black women for social justice.

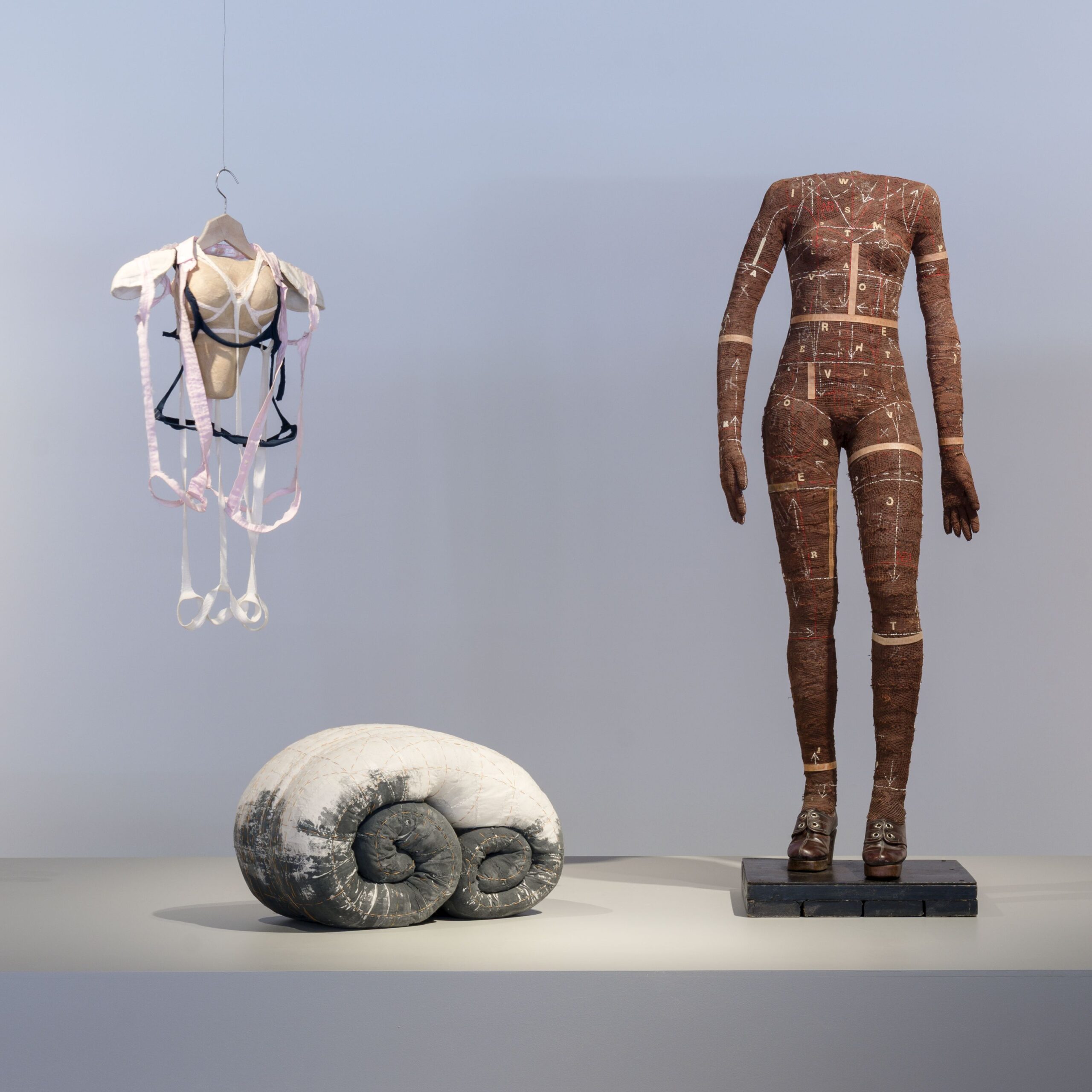

Põder, Anu

Anu Põder (1947–2013) was an Estonian artist who worked during the Soviet era and continued her practice after Estonia regained independence. She renewed sculpture and installation art by incorporating everyday objects and materials in her work. In the Soviet period, food and clothing were in short supply, so many women ended up sewing their own clothes. Despite this, strong ideals of fashion and beauty were applied to women’s appearance. In her work Space for My Body (1995), Põder cut used clothing to reveal their structure and hidden inside layers, leaving only the seams. Her sculptures often convey a sense of vulnerability, sensitivity and discomfort.

Rama, Carol

Carol Rama (1918–2015) was a self-taught artist who began her career in the mid-1930s. Her works examine sexuality, and the female body and its representations. The use of rubber in Rama’s art is rooted in her family history in Italy – her father owned a bicycle factory in Turin. In Rama’s works, rubber symbolises sexual vulnerability and the passage of time. The smooth, limp rubber tubes corroded by light and time can be seen to reference the human body – its strange, elusive and unspoken aspects.

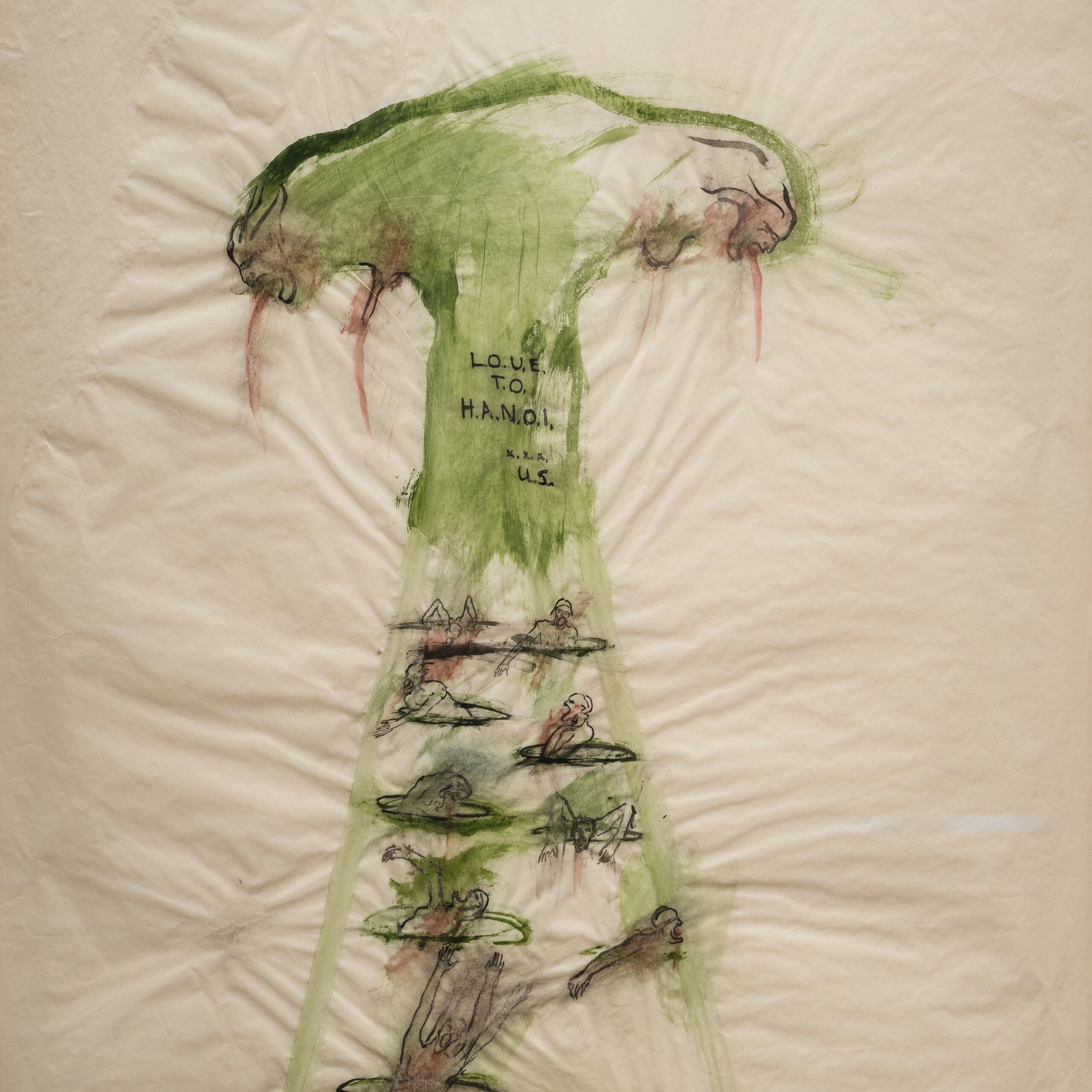

Spero, Nancy

Nancy Spero (1926–2009) was an American artist who addressed social, political and cultural injustices in her work. Her main themes were war, violence against women and women’s life cycles. Her War Series, created between 1966 and 1970, is based on television coverage of the Vietnam War. During this period, Spero abandoned painting on canvas and began making works on paper. She tore and rubbed delicate paper, thinning paint with her own spit to give the subject the intensity it demanded. Spero is known for extensive bodies of work whose seriality she disrupted by installing them in free form.

Storch, Tove

The work of Danish artist Tove Storch (b. 1981) can be seen as an ongoing exploration of possibilities within sculpture. Storch is drawn to the inherent language of materials that can be perceived through the body and the senses. She often leaves her works untitled to allow for interaction purely between the senses and the materials themselves. Bodies and clay are subject to the same laws of nature: both are equally shaped by time and gravity. Through her subtle visual approach and use of delicate materials, Storch can be seen to acknowledge these shared circumstances.

Vainio, Elina

Elina Vainio (b. 1981) is a Helsinki-based artist whose work explores the interrelations between humans and the materiality of our lived environment. Using textiles, sand and incense, she emphasises the fragility and interconnectedness of different life forms and the limitations of language in understanding the world. Her sand installation Deposits (2018) can be seen to suggest a place where traces of human activity are but a thing of the past. The work challenges us to consider the imbalance between the slow accumulation and rapid consumption of natural resources, and the kind of world we leave for future generations.

Exhibition Team

Exhibition Concept

Pilvi Kalhama

Curators

Nella Aarne, Pilvi Kalhama, Ingrid Orman, Tiina Penttilä

Project Management

Nella Aarne, Ingrid Orman

Technical Design and Construction

Jenni Enbom, Miika Kyyrö, Lasse Lindfors, Olli Lukkari, Lasse Naukkarinen,

Samppa Törmälehto, Joleco Oy, Subsonic Sound And Lighting Oy, Valge Kuup

Graphic Design

Päivi Helander

Typography

REVIEW MONO (Sophie Wietlisbach), CARDONE (Fátima Lázaro), ARTE POVERA Päivi Helander

Lighting

Jenni Salovaara

Conservation

Marianne Miettinen, Saara Peisa, Saku Asikainen

Framing

Antti Ratalahti

Registrointi

Jenni Enbom, Mereca Victorzon

Exhibition Texts

Nella Aarne, Tero Hytönen, Pilvi Kalhama, Ingrid Orman, Tiina Penttilä

Mobile Guide

Tero Hytönen, Ilari Strandberg

Audience Engagement and Events Program

Tero Hytönen, Reetta Kalajo

Guided Tour Design

Riikka Alanko, Ilari Strandberg

Design And Construction of Participatory Space

Maria Innola

Customer Service Design

Maija Eränen, Ilari Strandberg

Marketing and Communications

Iris Suomi, Helmi Tolonen

Photography and Documentation

Paula Virta

Service Sales, Visitor Surveys

Essi Huhtanen

EMMA Shop

Mira Alanko, Salla Engström

EMMA Customer Service and Guides

Translations

Mats Forsskåhl (Svenska), Tomi Snellman (English)

Furniture and light fixture loans

Pasi Pusa, Osto Ja Myyntiliike Kruuna

Thank You

Archivio Ketty La Rocca, Art Museum of Estonia, Galerie Gisela Capitain, Galerie Lelong & Co.,

Fondazione Maria Lai, Frittelli Arte Contemporanea, Haus der Kunst,

Hauser & Wirth, Liisi Beckmannin perikunta, Ludwig Museum of Contemporary Art,

Museum der Moderne Salzburg, Muzeum Susch, P420 Gallery, Sprüth Magers, Stedelijk Museum,

Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus und Kunstbau, Tartu Art Museum

The exhibition has received a state grant from the Finnish Heritage Agency