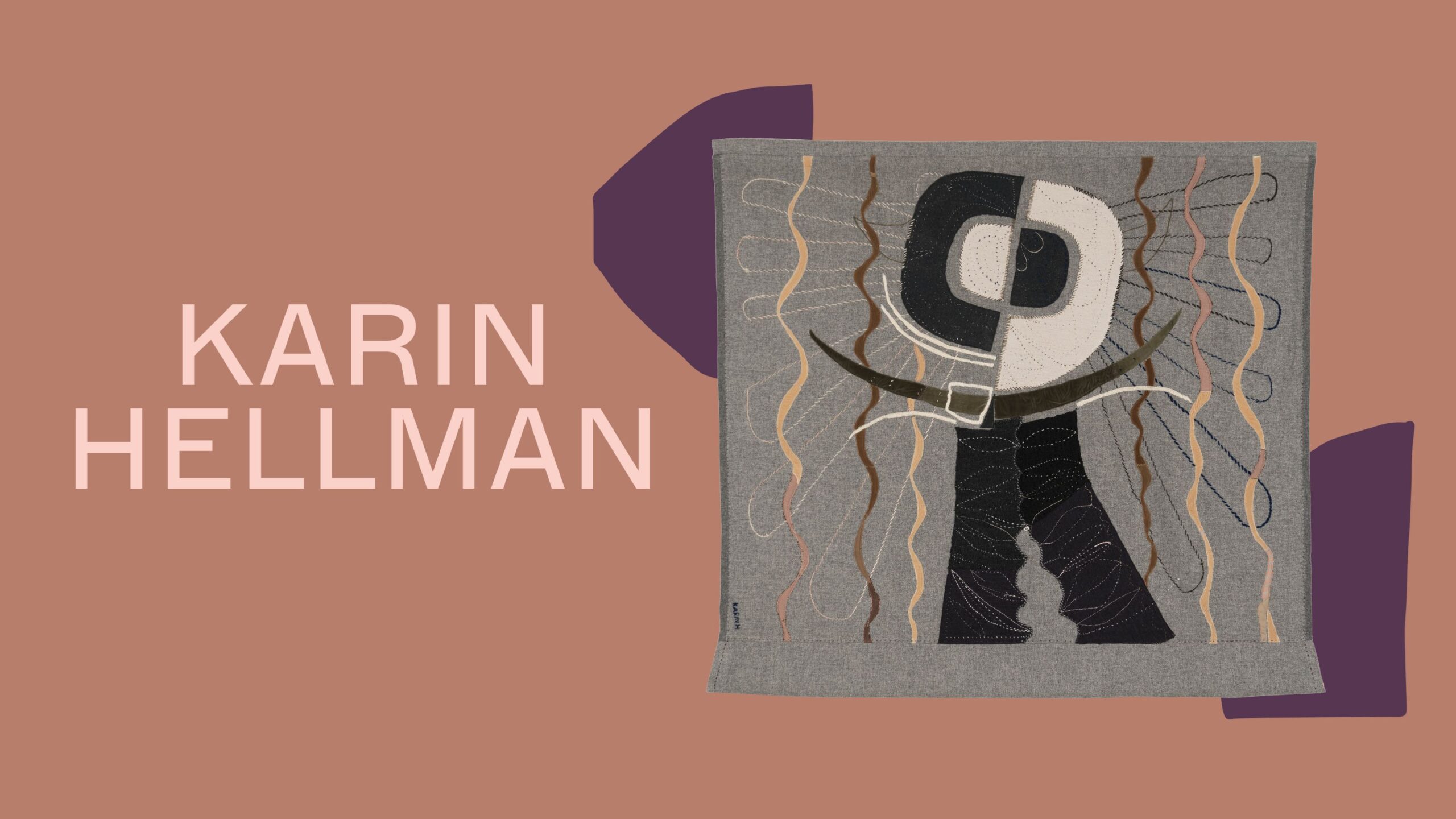

Espoo Museum of Modern Art

Mobile Guide to the Karin Hellman Exhibition

Karin Hellman (1915–2004) was an innovative and unconventional pioneer of Finnish modernism, yet her work remains unfamiliar to many.

In Hellman’s hands, materials found new and vibrant life: she combined natural materials, recycled textiles, and industrially produced everyday objects in her creations. She was one of the few Finnish artists to work predominantly with collage as her medium.

Hellman often worked on the floor of her studio, cutting old fabrics, sewing, and gluing fragments together. Her art reflects a liberated and intuitive approach to the creative process. Her interests ranged from the myths of various cultures to the phenomena of the modern world and visions of the future. A recurring motif in her work is the spiral, symbolising the cycle of life and spiritual growth. In many of her works, Hellman’s anti-war sentiments are also evident.

This extensive exhibition, featuring nearly 100 works, is the first major museum showcase of Karin Hellman’s art. The exhibition is primarily drawn from EMMAs collection.

Karin Hellman's Art

Themes

Karin Hellman’s oeuvre encompasses an extensive range of themes. Deeply attuned to the phenomena of her time, she often referenced world events in the subjects and titles of her works. Her themes also reflect an enduring interest in history, ancient myths, and visions of the future. Classical myths, Scandinavian mythology, and Biblical stories are juxtaposed in her art with imagery from prehistoric cave paintings.

She also explored more mundane as well as abstract subjects, which she imbued with a fantastical quality, echoing the mythological elements of her work. However, one of the most significant aspects of Hellman’s art was her focus on the materials themselves, which often became central to her creative expression.

Early Works

Karin Hellman’s early output, spanning the 1930s to the 1950s, consisted primarily of paintings. These works reveal her interest in diverse subjects, including still life, portraits, and interior scenes. She also explored themes popular at the time, such as the world of circus, which fascinated many Finnish artists. An example of that is her 1939 painting Clown.

In her still lifes, Hellman often depicted everyday objects, such as flowers in a vase. These subjects allowed her to experiment with composition and colour. She sometimes flattened the shapes of objects, a compositional approach influenced by Cubism, which sought to simplify and deconstruct subjects in innovative ways.

Materials

From the late 1950s onwards, Karin Hellman began exploring new materials in her work. Moving away from traditional painting, she increasingly employed collage techniques, sewing and gluing various materials into her artworks. Due to the experimental nature of her methods and the fragililty of the materials, her works are particularly susceptible to environmental stressors such as light exposure.

Hellman’s collages often incorporated materials from everyday domestic life. Rugs, fabric scraps, and knitted pieces frequently found their way onto her canvases. Discarded objects, such as the lenses of old glasses and rusty bolts, also became incorporated into her works. This connection to the Arte Povera movement underscores her innovative use of humble, everyday materials. Despite this shift, Hellman did not entirely abandon traditional techniques, as some collage pieces also feature drawing and painting.

The Spiral

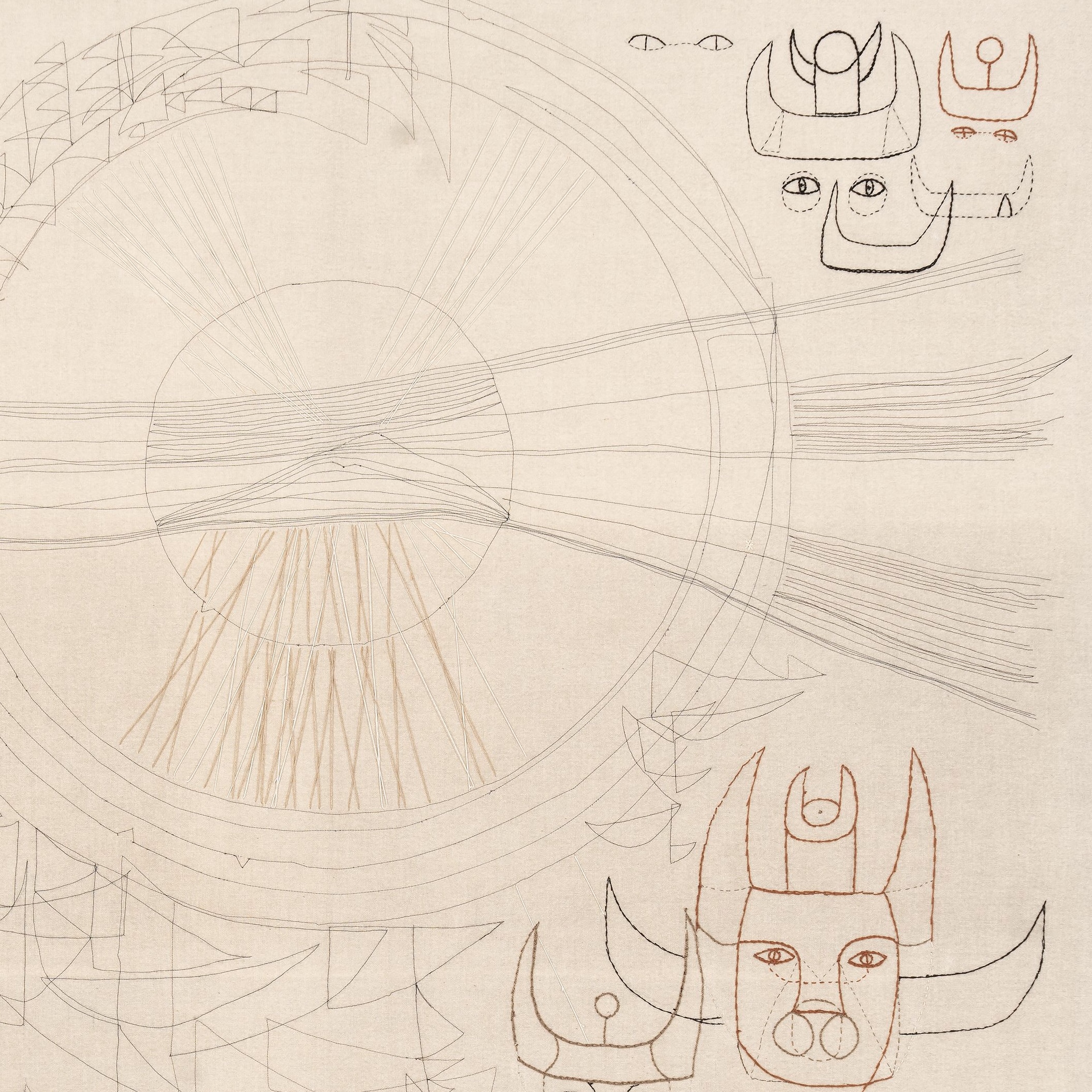

Drawing inspiration from myths and distant history, Karin Hellman frequently depicted a variety of symbols in her work, with the spiral being the most prominent. This motif appears consistently in her art from the 1960s onwards. In many pieces, the spiral takes centre stage, while in others, it recurs abundantly as a significant detail.

This ancient symbol is associated with cycles and the rhythms of life. In Hellman’s work, the spiral is intertwined with a wide range of themes. In works connected to nature and history, it can be seen to symbolise a balanced cycle. Conversely, in works addressing the threats of war and rapid technological progress, the spiral can evoke a sense of uncontrolled development. Hellman also placed great importance on the history of the materials she used, incorporating old family garments into her pieces. This practice can also be seen to reflect broader themes of circulation and continuity.

Karin Hellman's Works

Assault Vehicle 2181968

On 21 August 1968, Karin Hellman listened to a live radio broadcast from Prague, Czechoslovakia. The reporter described the Soviet invasion of the city, during which tanks violently suppressed the liberation movement known as the Prague Spring. Hellman created Assault Vehicle 2181968, capturing the brutality of these events as she heard them unfold. This artwork became a deeply personal anti-war statement for Hellman, who later donated it to the Amos Anderson Art Museum to ensure its preservation for future generations.

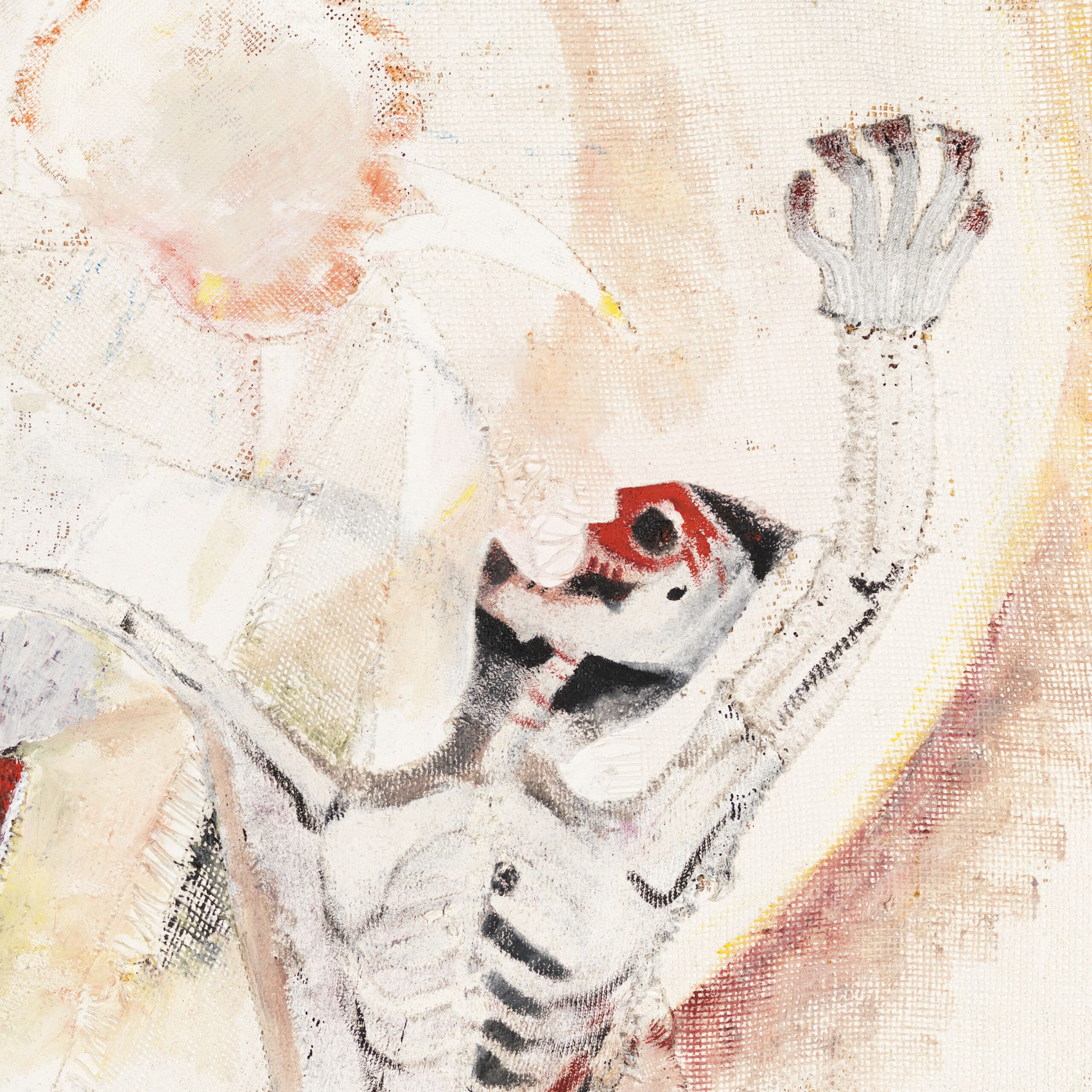

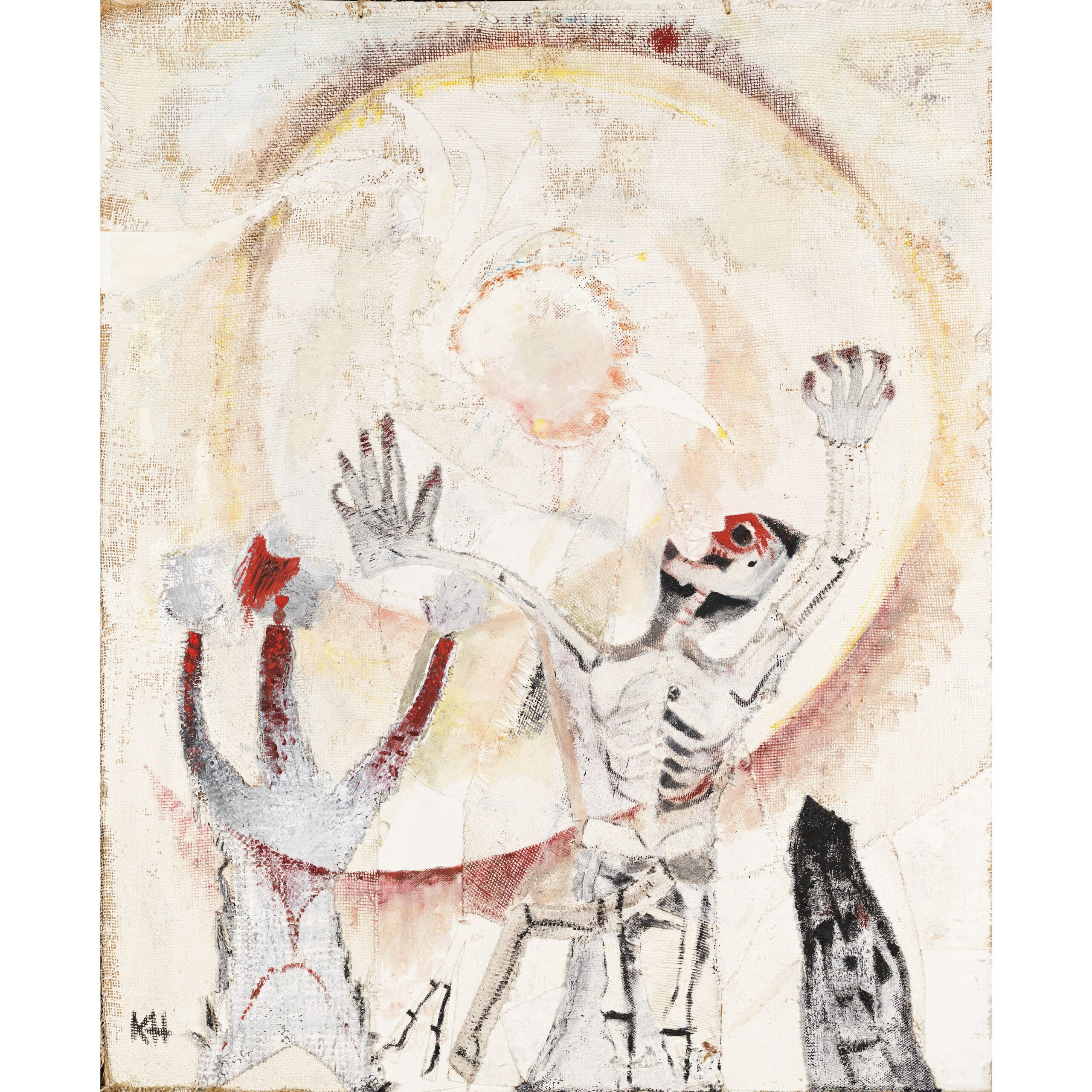

The Dance of Death in Our Time

The painting The Dance of Death in Our Time, AD 2000 reflects Karin Hellman’s contemplations on mortality and the fragility of humanity. It depicts two skeletal figures reaching towards a spinning spiral. While the theme is timeless, it can also be seen as a social commentary on Cold War –era fears of nuclear weapons. The spiral, a recurring motif in Hellman’s work, symbolises the cycle of life and death and their inseparable connection – here evoking the uncontrollable forces of destruction.

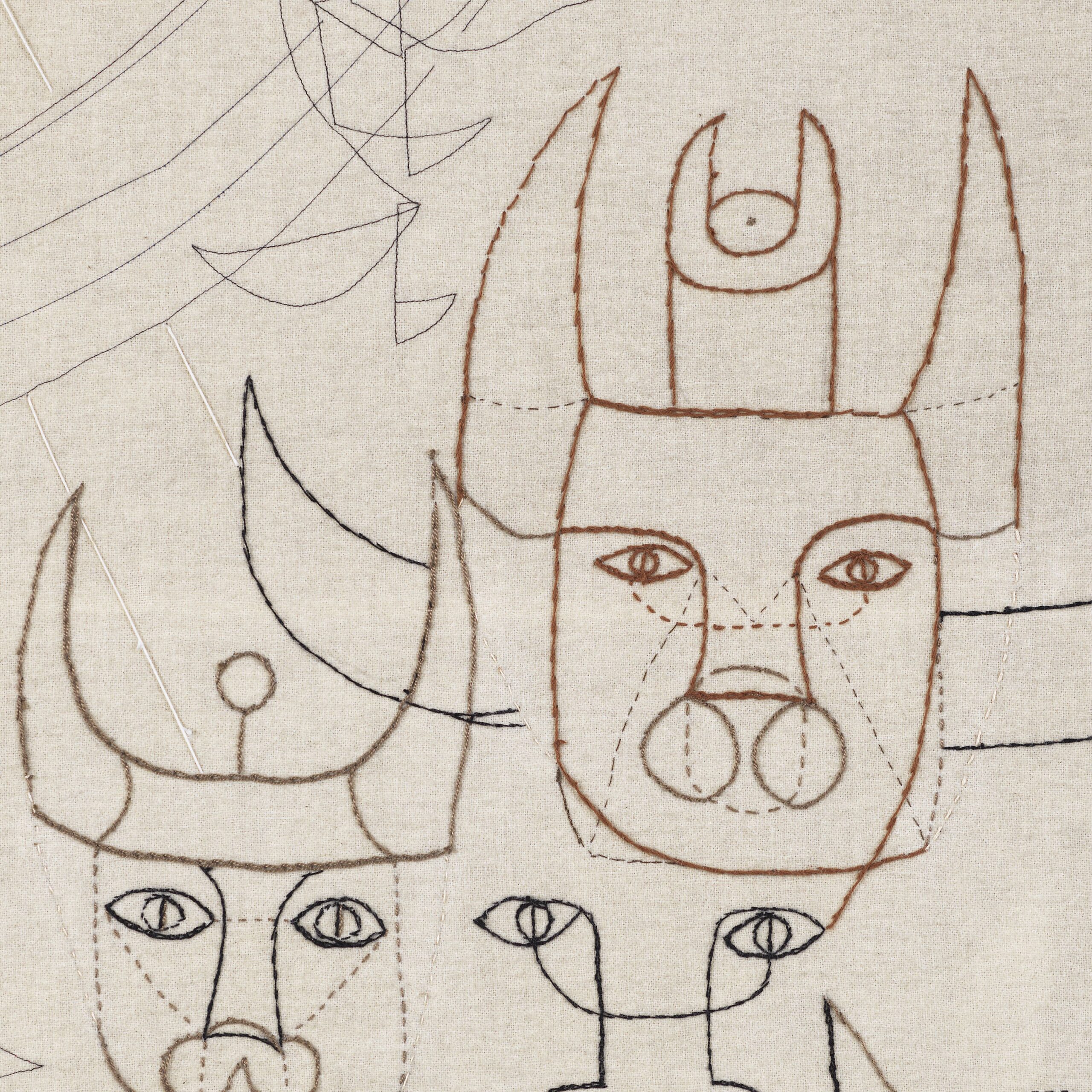

Girl and Rooster

Girl and Rooster is Karin Hellman’s first textile collage. While she began creating fabric artworks in the 1950s, these were not exhibited until the following decade. Hellman revisited the subject in 1983, creating a painting of the same name that closely mirrors the earlier textile piece. Despite the different techniques, both works share similar details. The horned, bull-like figures beneath the rooster in Girl and Rooster appear in several of Hellman’s works throughout her career.

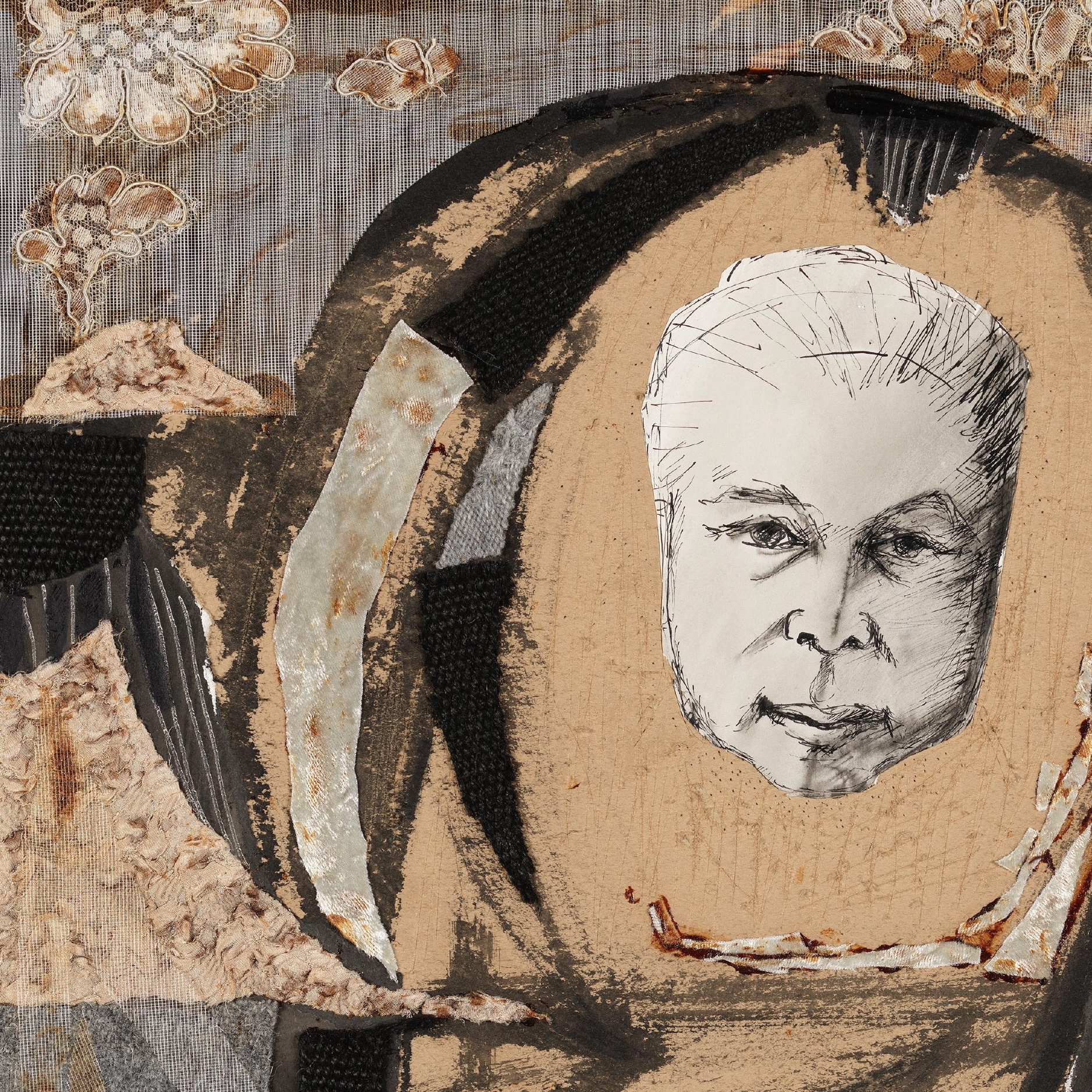

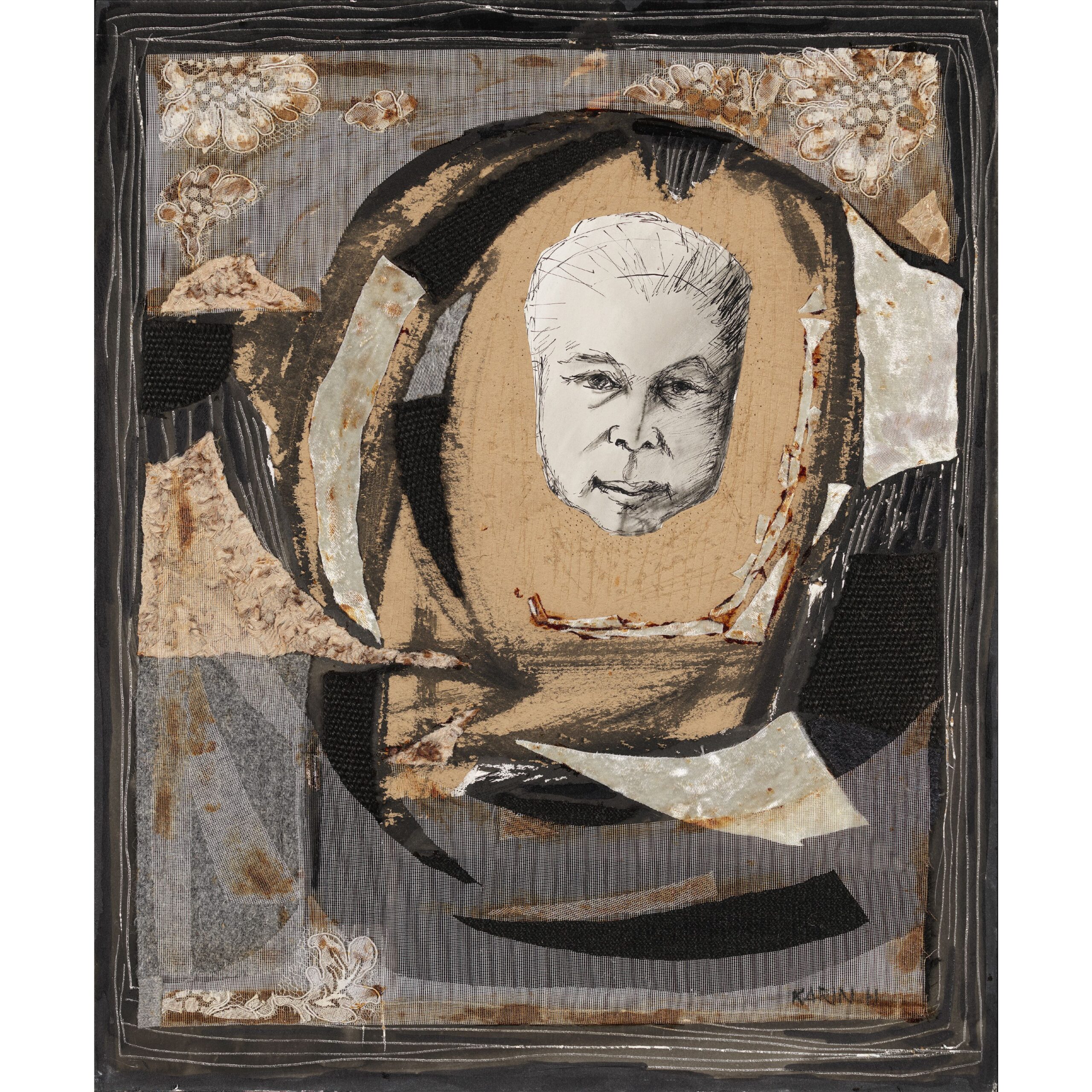

Grey Portrait

Hellman believed that reused materials possessed a unique beauty, enhanced further by their inclusion in artworks. In Grey Portrait, a drawn face on paper – likely a self-portrait of the artist – forms the focal point. The drawing is combined with tulle, lace, and fabric scraps, all glued to the background. Over time, the adhesive has aged significantly. Once transparent, it has discoloured, causing parts of the textile materials to turn brown.

In the Marquis’s Garden

There is a handwritten text by Hellman that sheds light on the background and creation of the work In the Marquis’ Garden. According to this annotation, the artist was inspired by the ruins of the Château de Lacoste in Provence, France, once owned by the writer Marquis de Sade. A stone taken from the ruins and incorporated into the artwork further connects it to this location. The Hellman family spent extended periods in the Lacoste area, purchasing a modest house there in 1964.

In Närpes

The title of this small collage, In Närpes, refers to a town in the Ostrobothnia region of Finland. The artwork features two human faces with the letters P and M on their foreheads. While the significance of these letters is not explicitly stated, they may refer to the Swedish words pappa (father) and mamma (mother). The background of the work consists of red woven fabric from Lapväärtti, which was originally used in national costumes. Lapväärtti was once part of the larger parish of Närpiö. Hellman used the fabric as a detail in several works. She also had a suit tailored from the same fabric, which is displayed in the exhibition.

The Last Sunset

Initially, Hellman envisioned The Last Sunset as a depiction of the sun setting on the horizon. However, as the work progressed, its focus shifted. The piece became a powerful anti-war statement, portraying the mushroom cloud of a nuclear explosion. It alludes to the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II, as well as the nuclear tests conducted until the 1990s. A circular hole in the mushroom cloud symbolises the void left by a nuclear explosion. It can be seen as representing emptiness and the end of everything.

The Sun Chariot

This large-scale collage, one of Hellman’s most significant works, draws inspiration from Norse mythology. According to ancient tales, the sun traverses the sky in a chariot. The sun chariot motif also appears in archaeological artefacts, often featuring the spiral shape familiar in Hellman’s works. The visual language of The Sun Chariot is rich, blending representational elements with a foundation of abstract geometric forms.

The Sun’s Oxen

Hellman enjoyed exploring ancient myths, in which the sun and oxen feature prominently. The ancient Greek epic Odyssey mentions the sun god Helios and his cattle of oxen. In Egyptian mythology, the bull was the embodiment of the sun god Ra. In Minoan culture on the island of Crete, myths tell of the Minotaur – a creature half-bull, half-human. In Hellman’s work The Sun’s Oxen, the bull figures adopt human-like characteristics. Her inspiration for the bull motif also stemmed from visits to prehistoric cave paintings in Lascaux, France, and Altamira, Spain, in the 1950s.

Tree

This artwork exemplifies Hellman’s innovative use of textiles to create her imagery. The piece is composed of fabric scraps, pieces of carpet, and yarns, all assembled with glue. Tree was one of the works exhibited at the São Paulo Biennial in 1967, as noted on the information label attached to its reverse. Other works shown in São Paulo included The Sun Chariot and the works Eve’s Eye and Adam’s Eye, both of which are featured in this exhibition.

Venus of Willendorf

Karin Hellman, deeply fascinated by archaeology, is known to have created three works inspired by the Venus of Willendorf, a small 30,000-year-old figurine of a nude female. In one of the exhibited works, Venus is placed at the centre of a spiral, while in another, she is surrounded by layered circles. Hellman viewed Venus as a potent symbol and even composed a poem celebrating her as a maternal figure and bearer of life. Drawing inspiration from ancient myths and mother goddess cults, Hellman explored the cyclical forces of life and death. The spiral and circles represent the layers of time that separate the present from history.

The Wheel of Fortune

The Wheel of Fortune is an emblem associated with the goddess of fortune in ancient mythology, representing the capricious nature of fate and the unpredictability of life. The title of the piece, The Wheel of Fortune, references the tarot card of the same name, and its vertical shape resembles a playing card. Central to the composition are metal objects, discovered near Hellman’s home by her daughter during dog walks. Most of these objects are rusty and intrinsically worthless. Despite the Wheel of Fortune has the power to grant great riches, the artwork has a stripped-down, unadorned appearance. Hellman enhanced the painted surfaces using the sgraffito technique, which involves scratching patterns through layers of paint.

Karin Hellman's Life

1915

Born 8 July in Pietarsaari. Parents: businessman Antti Wisuri and seamstress Alice Sarén. Four younger siblings.

1920–27

The family lives in Kokkola and Oulu. Karin attends a Swedish-language grammar school in Kokkola.

1934–38

Studies at the Central School of Art and Design in Helsinki to become an art teacher. Her instructors include artist Per-Åke Laurén and designer Arttu Brummer. During her studies, she gets to know Åke Hellman. Graduates as a teacher in 1938.

1938–47

Works as an art teacher in Tammisaari. During the Winter War (1939–1940), she works in a military hospital in Kokkola.

1939

Participates in her first exhibition, the Young Artists exhibition at Kunsthalle Helsinki.

1941

Marries artist Åke Hellman. Works in a military hospital in Kokkola.

1942

Son Karl Johan Hellman is born.

1947

Begins working as a drawing teacher in Porvoo, continuing until 1965. Daughter Åsa Hellman is born.

1949

Travels to Paris in the summer with Åke, visiting major art museums.

1951

Embarks on a four-month trip across Europe to Spain and back, visiting, among other places, the cave painting sites of Lascaux and Altamira.

1953

Travels to Italy.

1954

Holds her first solo exhibition at the Ville Vallgren Museum in Porvoo.

1955

Travels to Spain. Creates her first textile appliqué artwork, Girl and Rooster.

1957

Holds her first solo exhibition in Helsinki at the Art Salon.

1959

Moves into a new home, a studio house in Porvoo designed by architect Erik Kråkström. Karin and Åke work in a shared studio.

1961

Publishes a poetry collection, Hundloka (Cow Parsley). Exhibits collages for the first time in the international women artists’ exhibition at Club International Féminin in Paris.

1962

Rents a house with Åke in the village of Lacoste in Provence, France. In 1964, they purchase the house and spend summers there until 1994.

1965

Leaves her teaching job and becomes a full-time artist. Exhibits collages in Finland for the first time at the Fine Arts Academy of Finland’s exhibition at the Ateneum Art Museum.

1967

Participates in the São Paulo Biennial in Brazil. Exhibits at the Nordic Art Association’s exhibition in Stockholm.

1968

Participates in the Artists’ Association of Finland’s exhibition celebrating Finland’s 50th anniversary of independence in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

1970–80

Holds exhibitions at the Art Salon.

1981

A large textile work, The Old Sign, is unveiled in the Pietarsaari parish hall.

1982

A retrospective exhibition with Åke at the Amos Anderson Art Museum in Helsinki (37 of Karin’s works exhibited). Receives awards from the City of Porvoo and the Swedish Cultural Foundation in Finland.

1984

Holds her ninth and final solo exhibition at the Art Salon.

2004

Passes away on 25 February in Porvoo.

Exhibition Team

Curator

Tuomas Laulainen, Henna Paunu

Project management

Pernilla Wiik

Graphic design and visual identity

Päivi Helander, Aziza Lo

Technical design and construction

Anders Bergman, Jenni Enbom, Miika Kyyrö, Lasse Naukkarinen, Jari Rönkkö, Kari Siltala, Samppa Törmälehto

Lighting

Lasse Lindfors, Jenni Salovaara

Conservation

Saara Peisa, Taina Leppilahti, Saana Lopes, Viivi Vierinen

Framing

Seppo Laakkonen

Registration

Jenni Enbom, Mereca Victorzon

Exhibition texts

Laura Eweis, Tuomas Laulainen, Emma Lilja, Henna Paunu, Nanne Raivio

Editing of the publication

Emma Lilja

Mobile guide

Nanne Raivio, Helmi Tolonen

Audience engagement and events program

Reetta Kalajo, Nanne Raivio

Guided tour design

Riikka Alanko

Design and construction of participatory space

Maria Innola

Customer service design

Maija Eränen, Pekka Muinonen

Marketing and Communications

Iris Suomi, Helmi Tolonen

Photography and documentation

Ari Karttunen, Lilja Oey

Digitization and archival research

Helmi Hakala

Service sales, visitor surveys

Essi Huhtanen

EMMA Shop

Mira Alanko, Salla Engström

EMMA’s customer service and guides

Translations

Ditte Kronström (Swedish), Simo Vassinen (English)