Espoo Museum of Modern Art

Pilvi Kalhama: Colour Seduction – The Otherness and Freedom of Colour

How did Konrad Mägi’s idiosyncratic use of colour sit with the art scene of his day? What should a contemporary viewer make of his colourism? In her essay, Pilvi Kalhama uses Mägi’s works as a lens through which to examine the meaning of colour as part of the purpose of a painting. Instead of traditional, psychological or aesthetic interpretations of colour, she argues for enchantment and more diverse, freer analysis of colour, both now and in the future.

The very moment that the fiery flaming skies, meadows wafting in floral shades of pastel, or intense and varied cloud formations painted by the Estonian artist Konrad Mägi (1878–1925) reach the viewer’s retina, the subject of the picture becomes secondary. The rich masses of colour in Mägi’s paintings are seductive and intoxicating. Instead of recalling memories or images of a real subject, they transport us into a world of the unconscious, emotion and imagination. Colour in Mägi’s paintings is paramount, perhaps even their point of genesis. That is why we need interpretation of the colours in Konrad Mägi’s works, tools for diving into the deep, multicoloured heart of his art. I believe that an exploration of colour in Mägi’s work can help us approach his art in a holistic way that does justice to it. In this essay I examine Mägi’s relationship with colour, interpreting his colourism in light of selected examples of his work. I also speculate about the motives underlying his treatment of colour and try to contextualise it. In addition to Mägi’s ideas about colour, I also wish to verbalise how we in this day and age should approach colour in art.

It is time to remove the emphasis on form from its pedestal in painting and place it alongside an element of equal value: colour.

Blooming Branches (1917–20) is one of Konrad Mägi’s most sophisticated still lifes and a perfect example of a painting whose composition is founded on colour. The dark, dot-like brushstrokes establish an intensity and richness, even though the painting itself is flat and abstracted. The branches are from white and purple lilacs, and they appear in Mägi’s other still lifes. This is the last of Mägi’s still lifes, a masterful colour painting in the true sense of the term: the tones are bright and succulent yet restrained. Despite the fact that colour has a structural function in the work, the painting is free in its expressiveness. Comparing it with Mägi’s other still lifes, in which he puts a greater emphasis on careful composition, Blooming Branches seems like a celebration of colour. Yet it is quite clear that colour and form are completely inseparable in the painting.

The valuation of art has for centuries been based primarily on pictorial programme, structure, composition and the visual idiom of the artwork. From a contemporary perspective, the systematic subjugation of colour to other elements of art in research seems wrong – and also for the work described above. Every painter uses colour, and for many the process in fact starts from it. A good book too must have structure, but that alone is not enough to create a work of literature. Indeed, it is time to remove the emphasis on form from its pedestal in painting and place it alongside an element of equal value: colour. And how could a critic or researcher presume to place the constituent elements of an artwork in an intrinsically hierarchical order of preference at all? It would be tantamount to talking about his or her own conception of art, not the actual value of the artwork. A value hierarchy of the elements of painting, even if the idea were justifiable, could only be determined for individual works or artists.

In one of my previous essays from year 2006, I examined why colour in particular has so often been sidelined in artspeak and why the rapture of colour has for so long been denigrated in the act of viewing art.1 As historian Manlio Brusatin remarks in his A History of Colors, the academic view as far back as the 16th century was that colour is the polar opposite of drawing: whereas colour represents freedom and hope, drawing stands for compulsion and necessity.2 In his famous treatise On Painting (De Pictura) from 1435, Leon Battista Alberti wrote how colour depicts something other than itself.3 For centuries, therefore, colour has signified the unknown and undefined, whether for the artist or viewer. We are able to reach an almost total agreement and understanding regarding the aspects of form and structure in a painting. No wonder, then, that prior to the psychological and social theories of contemporary art and the insight that visual culture must be interpreted pluralistically, the discipline of art history focused primarily on form. Form was easy to talk about, and the associated trajectories of development in art could be pigeonholed according to common understanding. This begs the question, of course, about what we have not before seen or understood in art history. Mägi’s work is a powerful reminder that we must not forget colour. It is high time to rewrite art history from such a perspective.

We have contemporary art and the study of it to thank for the current situation in which we are able to reinterpret old art too with new eyes. I like to describe the contemporary use of colour that flies in the face of conventional colour theories as the era of post-colour theory. The idea is to point out how old colour theories and the ideology of purity and neutrality are deconstructed by current conceptions of colour.4 Instead of categorising the ways in which we define and read colour, we are coming to the realisation that colour must be interpreted anew for every work and in light of its culture. The situation might also be called an expanded field of colour. My formulation borrows, of course, from art theorist Rosalind Krauss’s famous article “Sculpture in the Expanded Field” from 1979 in which she rejects the categorical approach to art in which each medium is governed by formal rules. Krauss wrote her essay when the focus had begun to shift away from sculpture (raised quite literally on a pedestal) towards installation and earth art, an area quite different from traditional, normative, prescriptive and classificatory concepts or their simplistic analysis.5 Krauss’s thinking helps us see art – and colour – as a stage for multiple and diverse interests and interpretations. This kind of thinking makes us realise that we must indeed seek to avoid unidirectional, predetermined and predictable interpretations and instead focus our attention on the meanings of colour produced both at the moment of the painting’s creation and of its reception.

Physicality is an aspect of colour I also wish to emphasise. Colour in painting consists of mass. When Alberti stressed the importance of form and geometry, he justified it by the flatness, the two-dimensionality, of painting.6 With the advent of modernism, the physical massing of colour by someone like Mägi has gained ground, and the resulting work can no longer be considered two-dimensional. This means that a two-dimensional reproduction, such as an image on the page of a book, can never convey the painterly experience of colour in the fullest sense of the term. Because colour has a concrete, material aspect, we must ultimately always try to engage with the actual, physical artwork. In the form of paint, colour gives painting its physical manifestation and deepens our understanding of the marks made by the artist, their characteristic way of wielding the brush. Tracing the marks, we learn how paint was applied to the canvas and how the masses of colour stand in relation to each other in the dimension of depth. A mass of colour also connects with us haptically, through the sense of touch. When we perceive a sumptuous mass of colour on the canvas, our vision triggers an impulse to touch the work. And even if we don’t, we can still conceive how it would feel to touch the painting. It is this experience that the allure of painting – palpable colour painting in particular – is founded on. We have only come to truly understand this with the advent of contemporary art.

In writing about the allure of painting, Isabelle Graw has named this quality haptic longing,7 a concept that seems apt indeed in the case of Konrad Mägi and his immersive colour realities. The colour marks in his works are an expression of the vitality of his art, and their hapticity connects us and the artist. The resulting experience is an authentic and compelling one in which colour plays a vital role. One of the fundamental emotional states associated with art is enchantment. The idea is particularly suited to verbalising the experience of viewing Mägi’s exuberantly coloured canvases, for intense colour is precisely the kind of element that stimulates sensory perception of the work. Colour creates a special atmosphere, a connection between the subject and the object, also in Mägi’s work. The state of enchantment is in fact something we may actually expect a painting, as a physical object, to instil in us.8 When viewing Mägi’s sumptuously shaped and coloured clouds, certain attributes spring to mind: I sense energy, dynamic, vitality and life in the colours. They seem to suggest the idea of Mägi’s brush having moved across the surface of the canvas only a brief moment ago. At times his touch is lighter and merely applies a hue, while at others it is ponderous, powerful and specific. Without physical colour, it would not be so. An analysis of Mägi’s work as simply flat surfaces would never be able to describe the full experience of their worlds, for the paintings break away from the surface on which modern art has for decades been interpreted. The volume, mass and viewer’s multisensory experience seem to disrupt the pictorial plane, pulling us into the inexplicable world of the painting. The work is alive, and it is seductive.

In light of the viewing process described above, I venture to claim that the experience of colour includes universal elements common to all people and governed by rules. However, colour is not merely a relative property anyone can define at will; it creates meaning in the painting. Yet interpretation can never be encapsulated in unequivocal definitions: it does not cease, because the experience is rooted in subjective perception and intuitive associations. The interdependence and ever-shifting relationships of colours with each other and with the viewer makes them ephemeral and unstable.9 It is challenging indeed that colour does not admit an exact and shared definition. Interpretation is necessary, because experiences such as the one mentioned above cannot be described unambiguously, repeatably and with precision. What we can do is let ourselves be transported by the seductive experience of colour.

In view of the fact that Mägi grew up in a culture practically devoid of pictures,10 the viewers of his art may be curious where he acquired his inspiration for colours and why he so strikingly differed from his contemporaries as an artist. Mägi developed into a painter through drawing and illustration. But for him, illustrating magazines and books was not art, and he yearned for something that would elevate his work and help him rise above everyday reality. He wanted to become an artist and was convinced it could be possible by adopting a new medium, painting. As an art, painting differed from craftsmanship, and in the modernist framework it was viewed as a particular, intellectual, self-contained form of art that allowed artistic freedom.11 Although Mägi’s path to becoming a painter was not without obstacles caused by the period and the cultural context, many other aspects of his career at the time were rather conventional. For instance, he drew and made prints just like most of his contemporaries. And regardless of the movement a painter might choose as his or her own at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, every artist had received a similar education that was always based on drawing. Instruction in European art academies and independent salons was not comprehensive when compared with art education today, and it focused predominantly on drawing.12 It is symptomatic of the then-focus of art education that art schools in Finland too were known as Turku Drawing School and the Drawing School of the Finnish Art Society (commonly known as Ateneum). Thus, when Mägi first made the change from drawing to painting, he too, like all artists, had to redefine his stand towards contour from the perspective of his newly adopted medium. According to Finnish art historian Altti Kuusamo, emphasising colour as a kind of antithesis to the line was, in those days, linked with the possibility of adopting the identity of a bohemian artist.13 The idea that colour could have been more than “mere” matter on canvas is intriguing, that by being a medium for expressing otherness, it also embodied a link to the politics of the subject. It is fascinating to think that Konrad Mägi may have adopted such an idea; that he could have chosen colour painting as a means of constructing his identity as an artist.

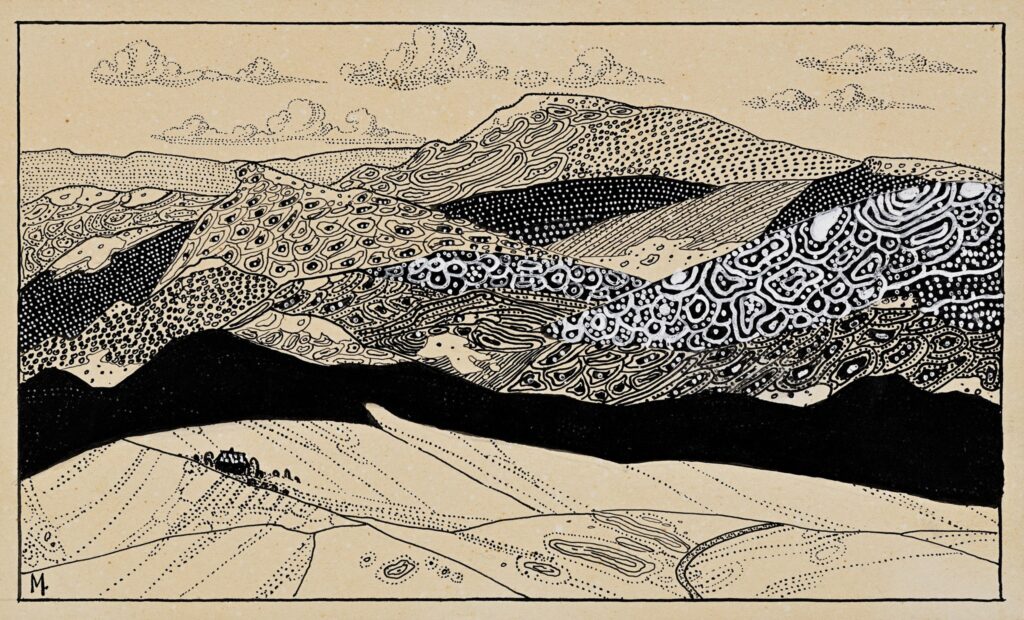

Konrad Mägi, Norwegian Landscape. Stylisation, 1909–10. © Art Museum of Estonia.

When he switched to painting, Mägi continued with the same natural motifs he had discovered in his decorative illustrations. With the new medium, however, the line gradually faded, and Mägi began depicting the forms of his subjects with free strokes of his brush. He combatted the overbearing grip of drawing quite consciously. In assessing the work of Akseli Gallen-Kallela, the great star on the firmament of Finnish art, he did so with reference to illustration. Back then, Mägi considered Gallen-Kallela more of an illustrator than a painter,14 effectively establishing the division and relative valuation of the two disciplines in his thinking. We catch a glimpse of Mägi’s philosophy of art in which he pits the principles of illustration and painting against each other. But while they were different categories with differing value for him, Mägi did not underrate the technical significance of drawing as a foundation for painting and colour. On the contrary, he was a staunch supporter of the theory of drawing and in this regard a typical representative of the educational trends of his day. To his pupil August Vesanto, he wrote:

[…] draw as much as you can […] and try to do it accurately and originally. The use of colour is not important, because when your drawing is good, the colours appear on their own.15

Learning to draw was evidently a necessary starting point for Mägi, with colour as the final objective, intrinsic to painting. Because colour was such a prominent aspect of Mägi’s art, it is exciting to discover that his ideas about it have come down to later generations in his correspondence. The letter shows that Mägi’s goal was to discover an unforced relationship with colour, and that he thought it would appear on its own, along with a growing skill. He makes no mention of formal theories of colour. Now there’s a colour philosophy. We may indeed assume that colour was for him a path to art and the key to becoming an artist.

In my eyes, Mägi’s palette differs from the predominantly restrained and down-to-earth tonalities in Finnish modernist art: the cheerier French palette never really took root in Finland. Dark “November” mentality, “Munch” anxiety and the expressionism-inspired disposition of the German Die Brücke group seemed a better fit for expressing the Nordic mindscape and the modern age. The mentalities of the north and south were clearly different in this regard.16 Although Mägi identified himself as an artist of the north, he chose his colour aesthetics from the latter: a French palette that was brighter, more colourful and purer. The choice was not well received everywhere in the Nordic countries; as I mentioned above, critical appraisals at the turn of the 20th century focused on form, with colour playing second fiddle. A case in point was Finland in the early years of the 1900s, when the definitions of art historian Onni Okkonen were regarded the voice of the official canon. In a review of an exhibition of Finnish art published in the Uusi Suometar newspaper on 7 October 1911, Okkonen remarked on the unwelcome “decorative” outcome of replacing the upright and austere northern motifs with decadent southern gardens and glowing colours.17 Decoration and colour were both frowned upon, although decoration was, in reality, not a wanton aesthetic but a profound method for detaching art from mere depiction of reality.18 As if to defy such a contemptuous attitude, the Septem group was founded in 1912, advocating the ideas of impressionism in Finland. The group’s members included, among others, Magnus Enckell, Verner Thomé, Ellen Thesleff, Yrjö Ollila and Belgian-English artist Alfred William Finch. Its agenda was to defend light and colour in art. One impulse for the founding of the group was a fiasco that took place in the 1908 autumn salon in Paris, where international reviewers criticised Finnish art for its gloomy austerity, that is, a lack of colour. Architect and art critic Sigurd Frosterus defended colour and the Septem palette, which he saw as containing aspects in contravention to an inherently Finnish way of using colour.19 However, the glowingly colourful work of many of the group’s artists has only recently come under deeper appreciation, such as Harri Kalha’s study of Enckell20 in which he examines the artist’s paintings while analysing the art-historical discourse of the age, reinterpreting both the analyses of the day and Magnus Enckell’s colourism. That disdainful attitude towards colour painting also suggests why a colour artist like Konrad Mägi was sidelined for a long time. A re-emergence of Mägi’s work can only happen in the wake of a rediscovery of the importance of colour.

Mägi was familiar with European art, having travelled on the continent on several occasions. Although many European artists had a keen eye for colour, the main topic of discourse was always form; evidently, colour was mostly a concern for those who came in contact with it in their practice. Mägi quickly adopted fauvism, the French style in which Matisse, Cézanne and Denis rendered the pictorial space with pure colour and the principle that in painting held colour to be a physical manifestation of internal observation.21 We may infer that Mägi had a predilection for painters of southern rather than northern sensibilities, although he may also have looked up to Russian artists, with whom Estonian artists had a historical connection. We do not know how keenly Mägi followed European art debates, but immediately before the criticism of Finnish art in Paris – when Mägi too was there – one of the leading colourists in European modernism, Russian artist Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944), exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants.22 Coincidence or not, that very same year, Mägi settled in Norway and painted his first indisputably colourist works.23 Kandinsky dedicated himself to colour in both his practice and his philosophy of art to an exceptional degree. Even the idea of direct influence does not seem far-fetched in view of a certain affinity in the palettes of the two artists. I am of course referring to the body of work that Mägi produced in Italy in the 1920s. The blue-toned paintings he made in Venice are characterised by the same mid-tone palette embellished with primary colours that had become a landmark of Kandinsky’s work in his Die Bleue Reiter period. Mägi may also have had an interest in Kandinsky’s thinking. One of the central figures in the emergence of abstraction in modern art, Kandinsky advocated a deliberate and conscious move towards expressive and esoteric colourism. In a radical text from the 1910s, he said that painting should not depict anything exterior to painting, the goal instead being “living pictures”.24

Konrad Mägi, Venice, 1922–23. © Enn Kunila’s Art Collection.

A re-emergence of Mägi’s work can only happen in the wake of a rediscovery of the importance of colour.

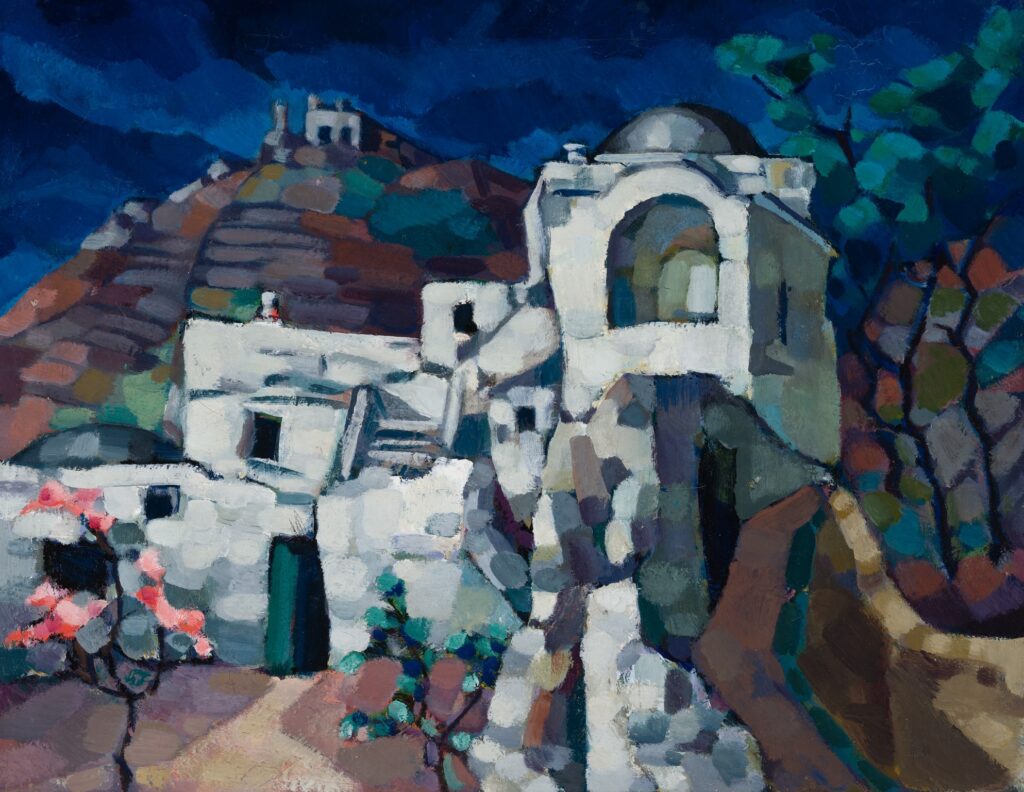

For the present essay, however, the most interesting aspect is Kandinsky’s theoretic thoughts about colour, admirably analysed by Finnish art historian Sixten Ringbom in his iconic book Pinta ja syvyys (“Surface and Depth”). Kandinsky organised Steiner’s colour ideas into a table in which colours corresponded to mental states: faint rose signifies longing, a more robust rose sacrificial attachment. Bright, mid-tone blue stands for piety, a paler hue devotion to high ideals.25 The interpretation of art, whether that of Mägi or more generally, would be rather wild if such definitions were taken at face value. The more important thing to remember is that professional artists thought about the meaning of colour in the context of their work and their aspiration to make the spiritual world visible. The connection between vitality and colour, so strong in Mägi, was one of the leading and early ideas of Kandinsky’s. Perhaps Mägi’s spiritual turmoil channelled itself as colours on the canvas. Emotions – indiscernible to us were it not for Kandinsky’s colour theory – may well be hiding behind natural motifs and a bright palette seemingly detached from all emotive content. In the 1920s when Mägi was in Capri, he began searching for an even more spontaneously deconstructed style exemplified in Ruins in Capri (1922–23). The structure of the work, created by cut-up fields of colour, suggests to me the art of Mägi’s day, but the influence behind the palette is definitely Kandiskian. Mägi used a dark palette with deep, luminous blues, especially in skies, which creates the impression of a nocturnal view.

Konrad Mägi, Ruins in Capri, 1922–23. © Art Museum of Estonia.

According to art historian Eero Epner, Mägi’s rich palette represents a counterweight to the austere and colourless life in Estonia; perhaps Mägi’s mind yearned for colours not found in Estonian culture or built environment, and as if to compensate for that lack the colours that appeared in his paintings are all the more exuberant.26 Mägi’s sphere of life – the inspiration and context that he painted – must have had an impact on his colour philosophy. We know that Mägi’s primary source of inspiration was nature and its colours. When I consider how ill at ease Mägi was in stone cities, I cannot help thinking that no European city, large or small, was capable of offering sufficient colour stimuli to his senses. So he went where he could find colour: Åland, the Norwegian and Estonian countrysides, and later Venice, Capri and rural areas in continental Europe.

The colours painters use are pigments; originating in nature, they are matter that links painting to the living world.27 Mägi used pigments to capture impressions of nature on canvas, but he used them in imaginative ways. In this he treaded the same path as Matisse, who stopped painting things in authentic, realistic colours. Matisse wrote in 1908: “To paint an autumn landscape, I will not try to remember what colours suit this season.”28 Mägi’s paintings convey a similar sense of the modern artist’s freedom to use colours to disengage from the depiction of actual nature. That freedom allowed the artist to add colours and hues to the natural palette to animate the vitality of nature in painting.

With a few early exceptions, Mägi painted no winter scenes. This too betrays a strong fascination with colour, the fundamental element of which is light. Because of light, nature was a wonderful starting point for his colouristic art. The luminescence in hundreds of Mägi’s paintings suggests they were painted in the north in summer. In them we can discern above all the annually recurring hues of meadows in May and the small, brightly coloured tufts of flowers glowing against a background of a bare shoreline. Mägi sought not only places where he could find colour but also places he could find light. It was in the bright, limpid, ever-present light of the north – inspired by the effusive colours of summer – that Mägi painted his most colouristically intense works. We may well have the colours of the tussocks and beaches of his native country to thank that Mägi was prepared to put up with the backwardness of the Estonian countryside and prioritise it over Parisian salons. The spectrum of colours in Estonian nature and coastline may be sparse and stark, yet by zooming in on its details, one discovers a most profuse palette of hues. And that was what Mägi painted – embellished with his vision – especially in the works depicting the Estonian countryside. I have often found myself stopping to look at the work On the Road from Viljandi to Tartu (1915–16). There is hardly a single naturalist colour on the canvas that might be found in such a landscape in reality: wandering along the dirt road, my gaze is drawn to the purple clouds, the ruddy fields and the copse of trees rendered in hues of turquoise, which invite me to immerse myself in the picture. The sense is of a countryside glowingly alive and gentle in the summer light. No wonder Mägi is such a central figure in the Estonian sense of nationality. Although Mägi’s colours void any direct likeness to a real landscape, I doubt anyone has captured the emotion of the Estonian landscape with greater depth and intensity than Mägi.

Konrad Mägi, On the Road from Viljandi to Tartu, 1915-1916. © Art Museum of Estonia.

We may assume it was the colour and light Mägi encountered in southern Europe that made him undertake a trip south. This time his destination was Italy. It has been speculated that Mägi travelled there because he knew about it from the journeys of his fellow countrymen, writer Friedebert Tuglas and artists Ants Laikmaa and Ado Vabbe. However, Mägi was drawn not by Italy’s culture but by Italian life and the climate.29 Considering the large number of works he produced in that period, one cannot but conclude that he fell in love with the colours and light of Italy. Mägi must have felt at home in the colourful Italian nature, because he wrote: “I think I must have a large dose of southerner in me.”30

I have let my eyes take in the pictures painted in Capri, and when I later recall the works in my mind, the memory paints them predominantly in shades of pink. In fact, in my imagination all of Mägi’s works acquire a reddish hue. While in reality there are many other colours in the works, pink has somehow established itself in my subconscious. Yet when I revisit the actual canvases from Capri, I can see how little pink there is in actuality, and still it has become the dominant colour in my mind. I can’t think of any other modernist painter whose work would have such a powerful presence of pink. While there admittedly are neo-impressionists whose pastel palette can be quite dominating, why does a splash of such colour seem so much stronger in Mägi’s works? It is the way he uses it. Generally speaking, an experience of thin and muted colours is soft, and a uniform tone actually hovers on the threshold of being a colour at all. By contrast, the clear variation of colour in Mägi’s work commands our attention, and the intense colours are overwhelming.31 Mägi’s pink can sometimes be just a single stroke of colour, an accent, yet it can steal one’s attention. In spite of the abundance of colours, Mägi retained a masterful control over them; he knew how to use accents sparingly. The pink in the Capri pieces is a precise case in point: a bright, feminine dot, like a sparkling jewel, but with high contrast, distinct and singular. This is where Mägi’s pink departs from that of most of his contemporaries. Pink was Mägi’s own effect, an exclamation mark, the dot on the “I”. And I can’t help thinking about it as a cipher for otherness. Pink is the colour of sensitivity, a far cry from the perceivably masculine, clear and straightforward primary colours. It is ambivalent and volatile in its meanings. On the atlas of colours, pink finds itself somewhere on the fringe and therefore allows greater freedom of expression and meaning.

In Mägi’s paintings of Saadjärv from 1923–24, pink has a very different, almost opposite meaning from the Capri pieces. If we didn’t know who painted them, we might erroneously see the contourless pastel colour fields as light and carefree. But because this is Mägi, we see that some of the works waver on the threshold of colour, which is exceptional for him. We know that these were the last works Mägi painted: he may have already been growing fragile, perhaps feeling his strength ebbing, maybe knowing his time was drawing near. With that thought in mind, we cannot avoid seeing these delicate colour fields as signs of fragility, of fading, of waning vitality.

Konrad Mägi, Saadjärv, 1923–24. © Art Museum of Estonia.

Only a few years after Mägi’s death, Kunsthalle Helsinki mounted an exhibition of international art from Estonia. The reviews were good, one might even say full of praise. On 22 March 1929, the Suomen Sosiaalidemokraatti newspaper published an extensive article about the featured artists, with Mägi mentioned specifically as a trailblazer. “His use of colour is intense yet quite delicious,”32 the paper wrote. Delicious is a fascinating choice of word and links yet another sense, taste, to Mägi’s colour painting. Be that as it may, attitudes towards colour had broadened, and Mägi’s captivating colourism was noticed.

Mägi’s landscapes are atmospheric renderings, not recognisable places. He never painted outdoors, relying instead on his memory and imagination. This too is something that needs to be held in mind when examining his colourism. Mägi’s colours reference a freedom that has no counterpart in visible reality. Colours enabled him to impart a mood on his works, and he established internal tensions in them compositionally. Colours were the medium through which he expressed himself as a modern, free painter. Undoubtedly, he also explored his subjective experiences in the works, but if so, he expressed them in a decidedly universalist manner. Or perhaps he cloaked his emotions in an esoteric colour code. The effect of his colours nevertheless is palpable, even to our eyes in the 2020s, and we can feel the moods of his colours as our own. In front of Mägi’s works, we find ourselves in a situation not unlike that of observing and interpreting contemporary art, where we allow colour to affect and transport us.

Mägi may have been quite conscious of the contentious nature of colour and its secondary status in the eyes of the critics of his day. It is possible that, coming from a country on the periphery of Europe, colour was a natural medium for him for finding his professional identity as an artist. It is possible that taking colour as the starting point of painting was a message – Mägi’s very own visual manifesto. That which is marginal or forbidden sooner or later becomes desirable, perhaps even coveted. Mägi knew, either consciously or intuitively, how to use this cultural trope, which in the early 1900s was known as bohemianism. In the years of his active engagement with painting, Mägi made colour an increasingly important part of his brand of modernism. Perhaps art was Mägi’s way of battling against the mediocre colourlessness of his culture or that of Nordic art. We can never know if his colourism was a statement, but what we do know is that his colours express a sense of otherness and non-belonging in the mainstream represented by most of his colleagues. As David Batchelor writes in his book about colours and fears associated with them, Chromophobia, Western culture has been quite active throughout the 20th century in purging colour from culture, devaluing its significance and denying its complexity.33 As a consequence, colour has become – and quite deliberately posited as – the polar opposite to rational Western order. Colour is something strange, something that tells us of the existence of instincts, of things that cannot be controlled. Although we do not know Mägi’s motives, colour in his paintings nevertheless is expressive of deviation from the norm. Thus, he belongs in the company of artists who have significantly, and at a very early stage, fractured normative thinking and culture.

Mägi’s colour worlds are open to interpretation and observation. The subjective aspect of colour perception implies a potential for alternative interpretation: it draws our attention to experience both rooted in the human mind and perceptible in the body. Giving room to the experience of viewing shifts the focus away from rational thinking. But as the analysis of Mägi’s pink hues shows, colour is more than just psychology: it is meaning. There is a powerful strand of colour psychology in art writing even today, and colour is often discussed in poetic and emotional terms rather than as consisting of cultural and semantic meanings. Neither approach is wrong, nor are either of them alone correct. That is why it felt necessary to write an essay about Mägi’s colours, their meaning to him and their connections to the art of his day – and to write about the temptation that Mägi’s colours awaken in us, the viewers. A topic that escapes all final truths, colour regains its topicality in the end; it is always open to new interpretation. All the usual seriousness of the interpretation of art can be forgotten when we talk about colour. It is time that colour made a comeback in the literary analysis of art. And who could be a better inspiration for and harbinger than Konrad Mägi?

English translation: Tomi Snellman

The essay was originally published in Konrad Mägi: The Enigma of Painting. Ed. Pilvi Kalhama. Helsinki, EMMA – Espoo Museum of Modern Art publications 69/2021. Online version editing: Emma Lilja.

NOTES & SOURCES

1 Kalhama, Pilvi 2006. ”Värin outo peittelemättömyys. Vaaleanpunainen (toisin)ajatteluna”. In Muotoutuva maalaus. Konteksteja ja kohtaamisia. Ed. Pilvi Kalhama. Helsinki, Kuvataideakatemia. The inability of traditional colour theories to intepret the meanings of colour emerges especially in the research and interpretation of contemporary art.

2 Brusatin, Manlio 1996 (1983), 19. Värien historia (Storia dei colori). Trans. into Finnish by Leena Talvio. Helsinki, Kustannusosakeyhtiö Taide. 3 Alberti, Leon Battista 1998 (1435), 125. Maalaustaiteesta (De Pictura). Trans. into Finnish by Marja Itkonen-Kaila. Helsinki, Kustannusosakeyhtiö Taide.

4 Kalhama 2006, 127.

5 See Krauss, Rosalind 1989. ”Sculpture in the Expanded Field”. In October, Vol. 8. (Spring, 1979).

6 Alberti 1998 (1435), 58–89. The first book of De Pictura discusses geometry, without which an artist cannot become a good artist.

7 Graw, Isabelle 2018, 20. The Love of Painting. Genealogy of a Succes Medium. Berlin, Sternberg Press.

8 Kalhama 2006, 139.

9 Foti, Véronique 1993, 300. “The Dimension of Color”. In The Merleau-Ponty Aesthetixs Reader. Philosophy and Painting. Ed. G.A. Johnsson. Chicago, University of Minnesota Press.

10 Epner describes the picture-poor culture in 20th century Estonia in his essay “Konrad Mägi’s Conception of Beauty” in this volume.

11 Graw 2018, 11–12, 26.

12 Kuusamo, Altti 1998, 20, 25. “Akatemian idea ja taiteiden järjestelmä”. In Silmän oppivuodet. Ajatuksia taiteesta ja taiteen opettamisesta. Kuvataideakatemia 1848–1998. Ed. Riikka Stewen.Helsinki, Kuvataideakatemia.

13 Ibid. 25.

14 Mägi, Konrad. Undated letter from Paris. Epner 2018, 150. English translations of the letters are available at: https://konradmagi.ee/en/letters/ (accessed 15.5.2021) and from the exhibitionpublication Epner, Eero 2018. Konrad Mägi 1878–1925. Tallinn, Art Museum of Estonia. The references to quotes in this essay are from the printed book, which, having page numbers, is easier to consult.

15 Ibid. Letter dated 16.12.1907. Epner 2018, 148.

16 Kallio, Rakel 2001, 23. “Estetiikkaa ja tunteita”. In Pinta ja syvyys. Varhainen modernismi Suomessa 1890–1920. Ed. Riitta Ojanperä. Ateneum Art Museum publications no 24. Helsinki,Ateneum Art Museum / Finnish National Gallery.

17 Okkonen, Onni 7.10.1911. “Suomen maalaajain ensimmäisen vapaanäyttelyn johdosta”. Uusi Suometar.

18 For more on the philosophy of decoration, see my essay “The Supernatural Power of Painting:Konrad Mägi’s Symbolist Philosophy” in this volume.

19 For a detailed account of the events and reception in connection with the Autumn Salon, see Marja-Terttu Kivirinta’s dissertation. Kivirinta, Marja-Terttu 2014, 12–16. Vieraita vaikutteita karsimassa Helene Schjerfbeck ja Juho Rissanen Sukupuoli, luokka ja Suomen taiteen rakentuminen 1910–20 -luvulla. Helsinki, Unigrafia; O’Neill, Itha 2015, 36. “Taide elämänasenteena”. In Sigurd Frosterus. Taide elämänasenteena. Amos Anderson Art Museumpublications, no. 95; Valkonen, Markku 1999, 102–105. Finnish Art over the Centuries. Helsinki, Otava.

20 Kalha, Harri 2005. Tapaus Magnus Enckell. Helsinki, SKS.

21 Sariola, Helmiriitta 2001, 195. “Väri”. In Pinta ja syvyys. Varhainen modernismi Suomessa 1890–1920. Ed. Riitta Ojanperä. Ateneum Art Museum publications no 24. Helsinki, Ateneum Art Museum / Finnish National Gallery.

22 Becks-Malorny, Ulrike 2002, 193. Wassily Kandinsky 1966–1944. The Journey to Abstraction. Köln, Taschen GmbH.

23 I discuss Mägi’s colours in Field of Flowers with a Little House (1908–10) in my essay “Sense of Style – Konrad Mägi’s Modern Conception of the Image” in this volume.

24 Originally a lecture given in Cologne: Kandinsky, Wassily 1996 (1914), 98. In Art in Theory 1900–1990. An Anthology of Changing Ideas. Ed. Charles Harrison & Paul Wood. Cambridge,Massachusetts, Blackwell; Becks-Malorny 2002, 94–95.

25 Ringbom, Sixten 1989, 64–65. Pinta ja syvyys. Esseitä. Helsinki, Kustannusosakeyhtiö Taide.

26 Epner, Eero 2017, 357–358. Konrad Mägi. Tallinna, Enn Kunila / OÜ Sperare.

27 Graw 2018, 23.

28 Matisse, Henri 1996 (1908), 75. “Notes of a Painter”. In Art in Theory 1900–1990. An Anthology of Changing Ideas. Ed. Charles Harrison & Paul Wood. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Blackwell.

29 Epner 2018, 108–109.

30 Ibid., 109.

31 See e.g. Elfving, Taru 2006, 150. “Värillä väliä”. In Muotoutuva maalaus. Konteksteja ja kohtaamisia. Ed. Pilvi Kalhama. Helsinki, Kuvataideakatemia.

32 Siippainen, E. 22.3.1929. Suomen Sosiaalidemokraatti. No. 81. National Library of Finland digital collections. https://digi.kansalliskirjasto.fi/ (accessed 24.4.2021).

33 Batchelor, David 2000, 22–23. Chromophobia. London, Reaktion Books.